Imagine two classrooms. First grade, January.

In one classroom, children are sitting quietly at desks, following in a workbook as a teacher leads a lesson in science. The children are (supposed to be) answering a question right now about how bees help in pollination from the video they all just watched from their seats. The teacher walks around, redirecting, helping to erase errors, pointing to the line children should be writing on in the book. There is some focus, quite a bit of fidgeting, and many reminders from the teacher to be on task.

This is direct instruction.

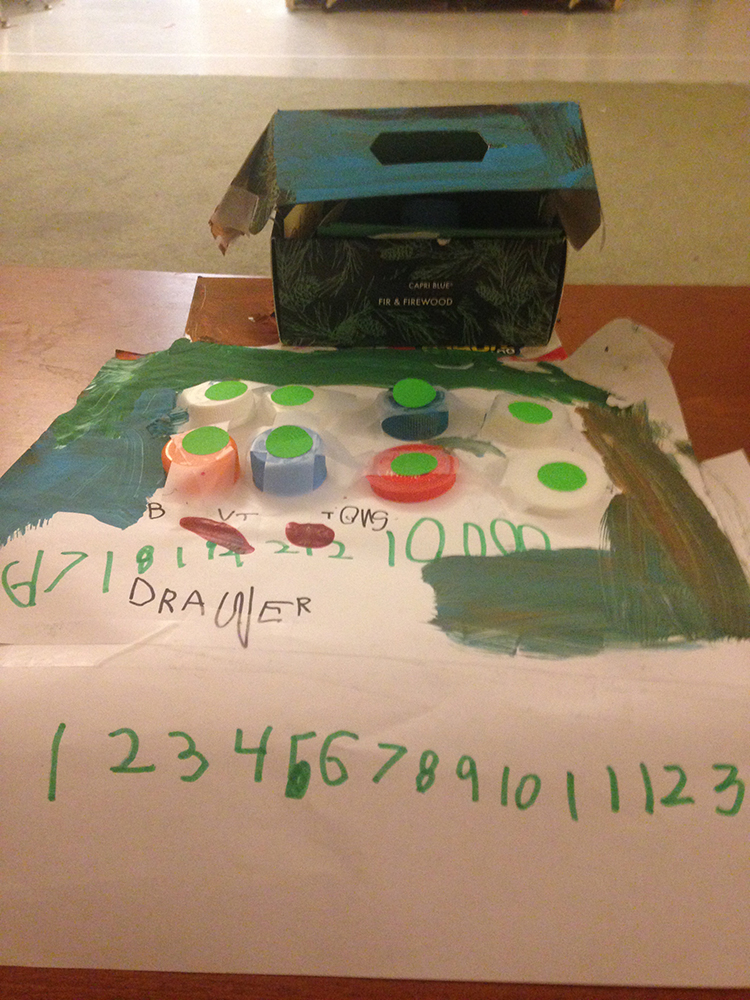

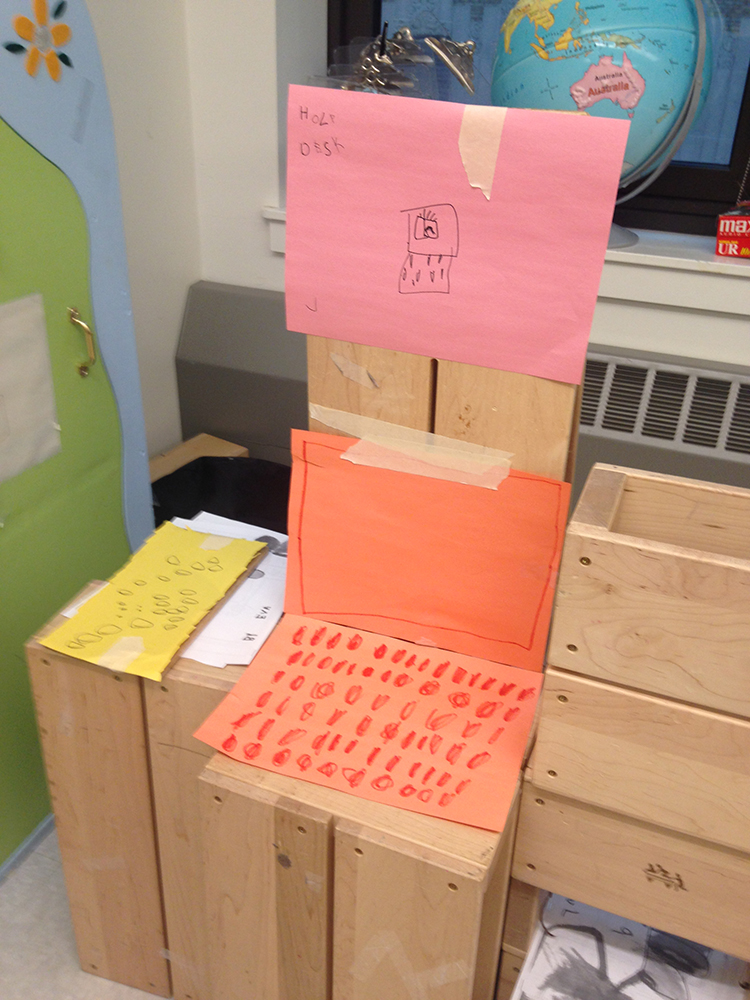

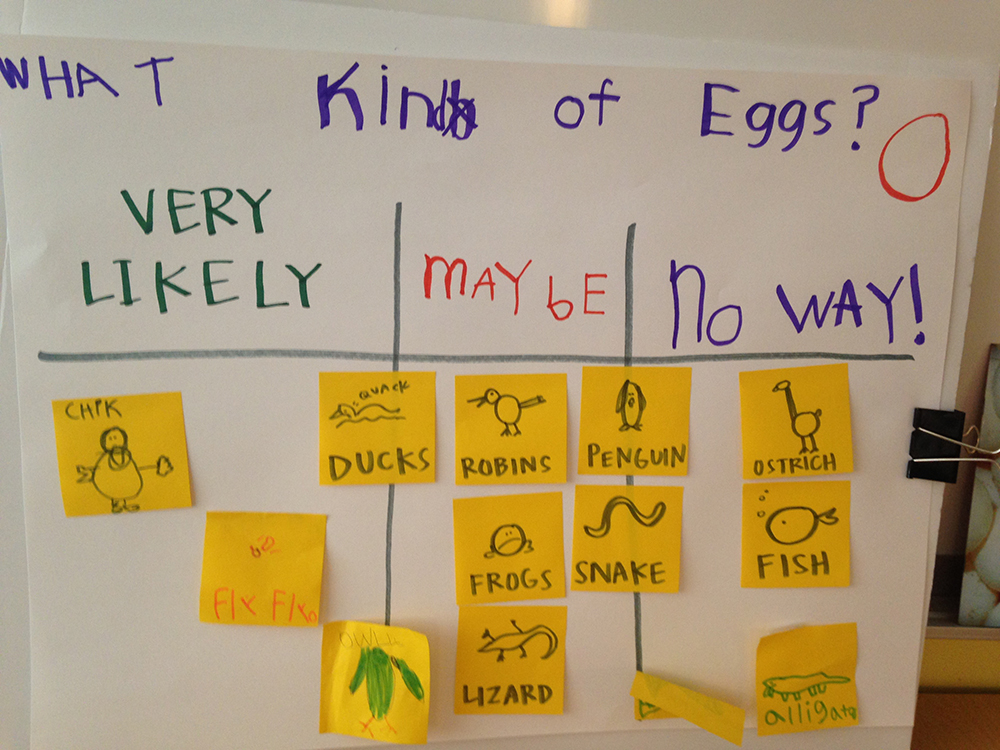

Now imagine another classroom, the children heard a read-aloud about bees while sitting together on the rug, and now they are off investigating. Some are trying to make a bee out of cardboard and tape, another group is looking closely at flowers while they represent the petals in black line drawings. Yet others are looking closely at the other books on bees, and a few are making “Carful Bees” signs to hang by the plants outside. The children are talking and moving and laughing, the teacher is asking questions, directing children to use an alphabet chart to help with spelling, and facilitating how to problem-solve attaching a popsicle stick stinger. The room is busy, alive, messy with thinking.

This is play.

When did play get cast as an enemy to learning? When did we begin to doubt the brain’s ability to learn from doing and exploring? When did we transfer trust from children and teachers to curriculums printed in bulk?

Is play really the barrier to learning? Do we imagine children at play put up learning walls in their minds, resistant to acquiring any new possibilities or ideas or information? It is well established, and for many years now, that play is one important way children learn. Most recently, Jackie Mader’s (2022) analysis of existing research found,

“[W]hen children ages three to eight engage in guided play, they can learn just as much in some domains of literacy and executive function as children who receive direct instruction from a teacher or adult. . . . The study found children also learned slightly more in some areas of numeracy, like knowledge of shapes, and showed a greater mastery of some behavioral skills, like being able to switch tasks.“

Say this out loud to yourself. Reread it. Children at play learn just as much and sometimes more than children engaged in direct instruction. This does not mean that every single thing we do has to be taught through play, but rather that play itself is an aid to learning, not a distraction.

If learning is not the core issue, then what is? Why are adults (and the curriculums they write) so afraid of children’s play? If our curriculums are research based, why do they choose to ignore this research?

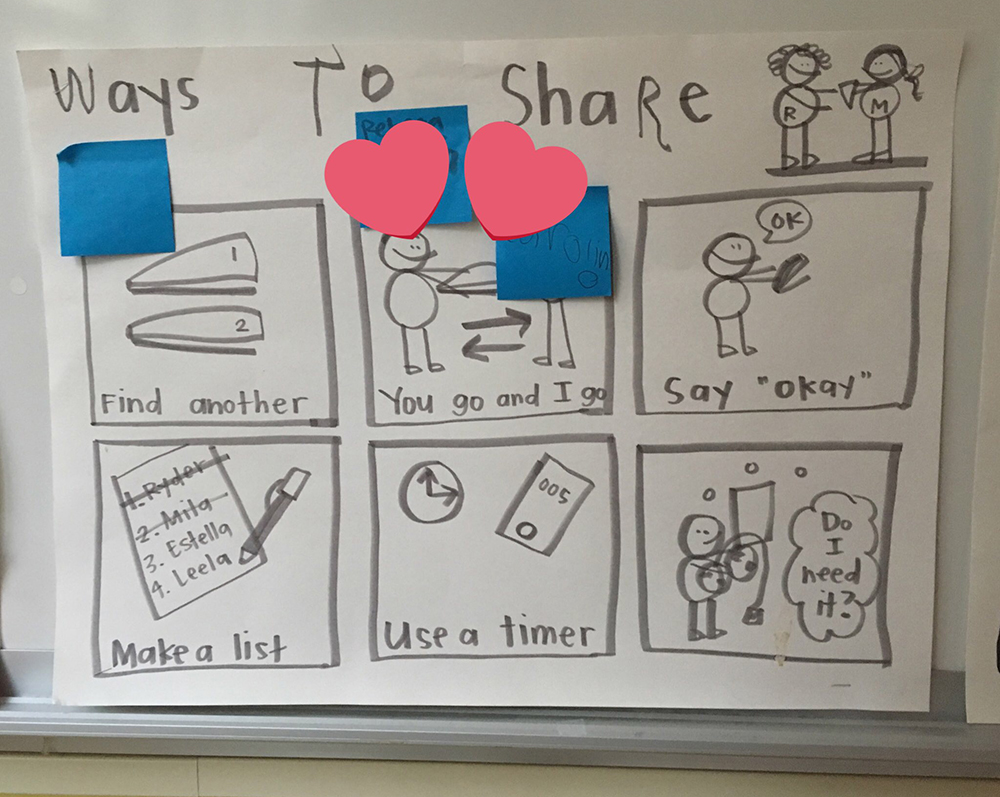

Is it because children at play learn a suite of other skills? They gain confidence and independence, they innovate and problem solve, they wonder and diverge. Children at play invent the future, they do not replicate the present. Children at play are agents of change. Children at play are creators of community, natural collaborators. Children at play are free and independent thinkers.

Is the reductive attitude toward children’s play a form of control and oppression? In the data-driven effort to prepare children for the future, are we choosing methods that prepare them for a future of compliance?

Think back to the classroom examples above. It is not a free-for-all of block throwing and indoor wrestling and general chaos. It is a facilitated exploration of a big and interesting concept: How does a bee’s structure facilitate its function? How do bees and flowers work together for the miracle of pollination? Play is not the learning, play is the method for learning. Play is also the method for a way of thinking, of self-confidence, of collaboration, of critical thinking.

And that brings us to the crux of the whole issue. Play is a choice we, the adults, can make. We can work toward many foundations, standards, and concepts through a thoughtful curation of materials and our interactions with children at play. Play is our instructional method, not our outcome.

So where do we begin?

- If you do not have any open-ended or exploration time in your day, start first by looking at your social studies and science content. Is there a way to move from hearing or seeing to doing? Could children use things like loose parts, makerspace, or art to try to understand ideas and develop wonderings?

- Educate yourself more on guided play and the research behind it. Look up Kathy Hirsh-Pasek and read everything you can.

- Help others understand that play is a method, not a time of the day, and that in using this method, you are working with how the brain learns best.

There is a quote by Annie Dillard from her book The Writing Life (1990) that says, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing” (p. 33).

With that as a call to action, how do we want to spend our lives? And how does that impact how we spend the next hour? When we choose to honor children’s play, we choose a future of change, hope, and possibility for something better.

References

Dillard, A. (1990). The writing life. Harper Perennial.

Mader, J. (2022, March 24). Kids can learn more from guided play than from direct instruction, report finds. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/kids-can-learn-more-from-guided-play-than-from-direct-instruction-report-finds/