Elementary teachers must actively challenge the colonial standards and curriculum, beginning with taking the time to reflect and complicate curriculum—decolonization is not a destination, but rather a process that educators must continue to engage in order to resist becoming complacent in perpetuating colonial ideology.

—Carolina Valdez, 2020, p. 592

As a teacher who is actively working to complicate their classroom curriculum, I often think about how to bring in different voices in order to ensure a variety of perspectives are represented. My own identity as Mexican American plays a large role in my classroom. When I was eight years old, my family moved from Mexico City to Austin, Texas. This change introduced me to a whole new culture and language; I had to adapt and assimilate in order to survive. Through my journey in the K–12 system, I found myself purposefully rejecting my Mexican heritage in order to fit in with my classmates. However, I got to the point where I felt disconnected and alienated—from my family back home, my language, and myself. I began to work on reconnecting to a part of me that had been buried deep inside by a small, scared little girl. I am determined to ensure that my students never have this experience in the classroom, that every day their lived experiences are valued and represented in my classroom.

Although I am Mexican, I did not grow up in connection to Indigenous ancestors. Nonetheless, I knew that part of reconnecting to my own culture needed to occur simultaneously as I explored native Indigenous identities around me. Part of this exploration included attending the Tānko Institute, a teacher education program at Texas State University, hosted by the Miakan-Garza Band of the Coahuiltecan tribe. The institute focuses on spreading Xinachtli, a land-based Indigenous pedagogy. As I worked to understand how to bring this knowledge into my classroom, I decided that books were the best way to bring in Indigenous perspectives and ensure that the students in my room, many of them with Indigenous backgrounds, felt represented and understood. By bringing in Indigenous voices through Indigenous authors, their thoughts, ideas, and knowledge are centered in the curriculum. It allows us to ensure that students are having authentic experiences with these ideas.

This unit is a product of collaboration between my mentor teacher and me, as well as the students we taught that year. As we wove different threads together, we noticed three essential components of Indigenous teachings emerge: water as a life form, the earth as a teacher deserving respect, and land as something we must actively connect with.

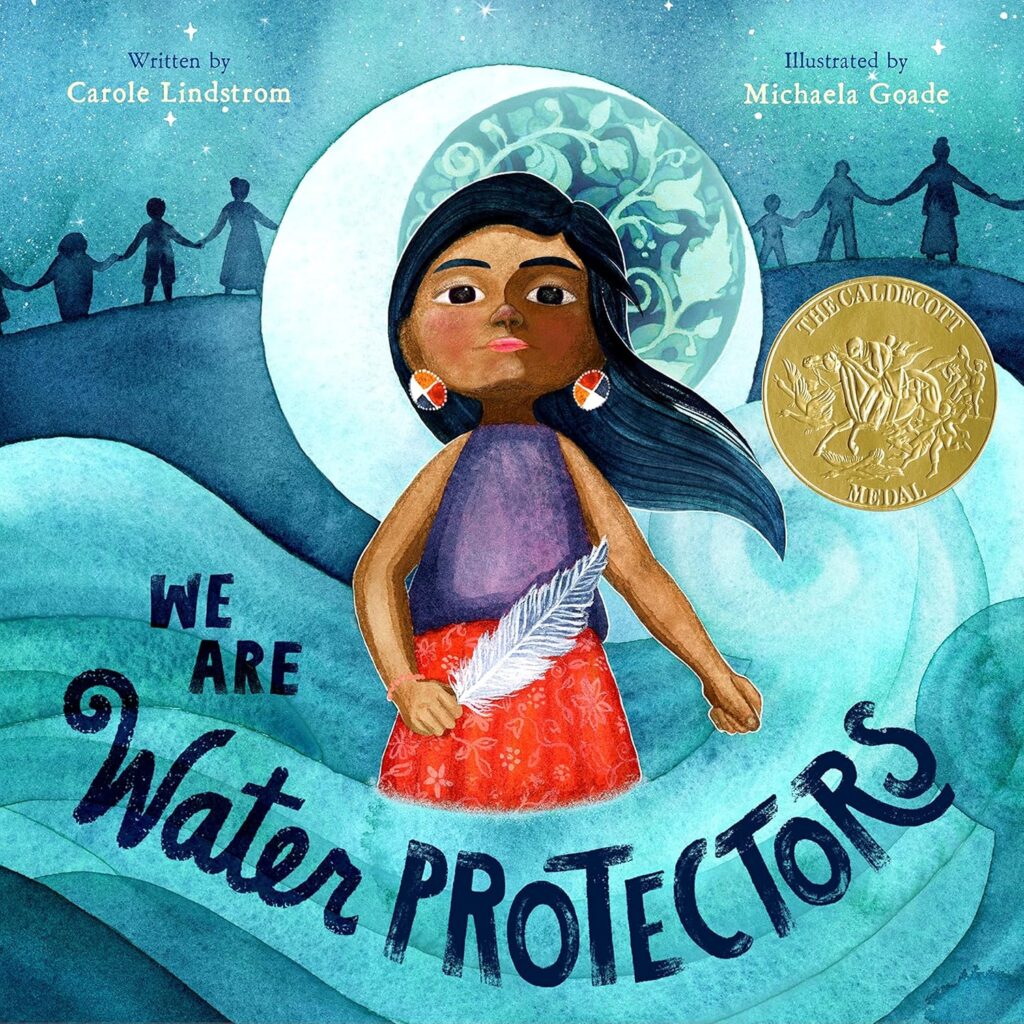

Water is Life

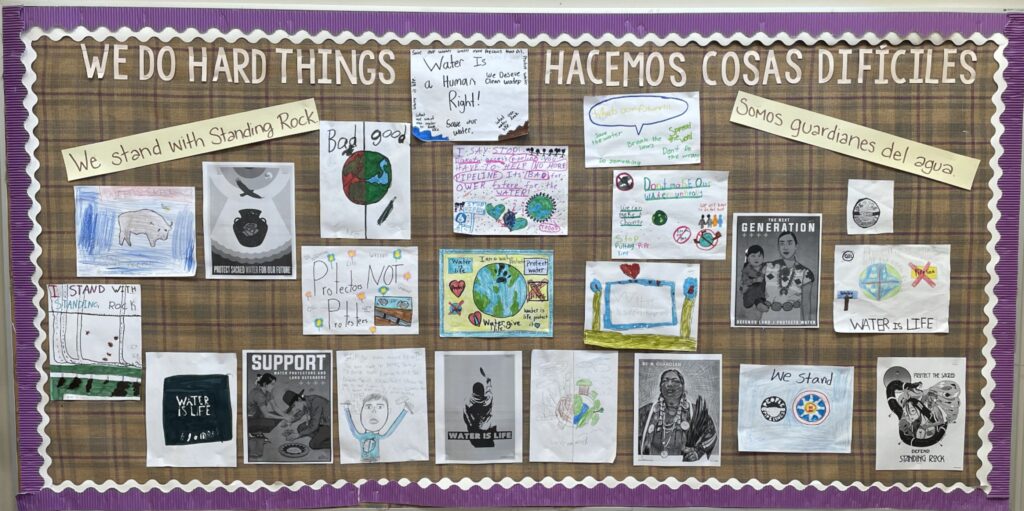

Unbeknownst to me, our unit started before I even started conceptualizing it. In the fall, our class read We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstorm, where students worked to analyze the poetic elements of the book as part of a poetry unit. However, as we moved through the unit, students began to notice the importance of water to Indigenous people, not only due to its essential nature for survival, but as a holder of knowledge that passes down wisdom through generations. It was through this discussion that we began to talk about Onion Creek, which runs right behind our school. Together, we discovered that the Coahuiltecan people took (and continue to take) care of the land around our school, including the creek. The creek water is considered sacred to them due to their origin story. We discussed the importance of taking care of water sources, not only for our well-being but out of respect and empathy for the Indigenous people who have cared for the water for thousands of years. The book led us to learn about the Dakota Access Pipeline and Standing Rock. Students took on the role of activists and connected with the message of the book by writing activist posters to show solidarity with the Ojibwe community.

The Earth as a Teacher

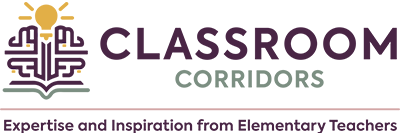

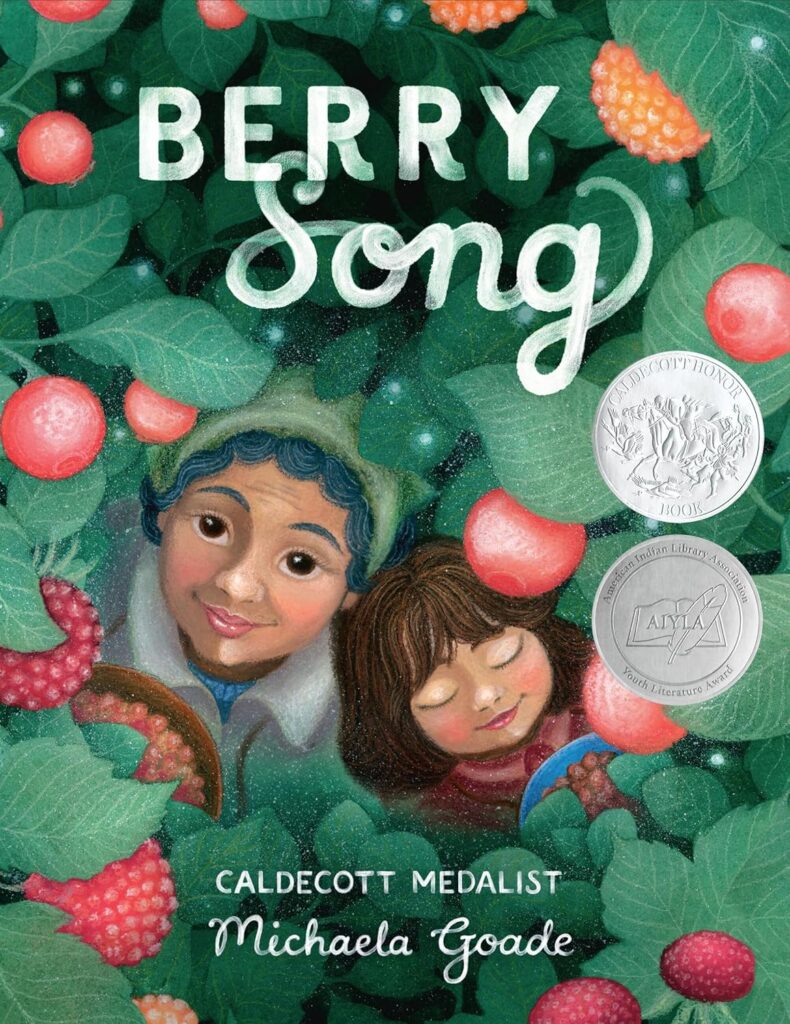

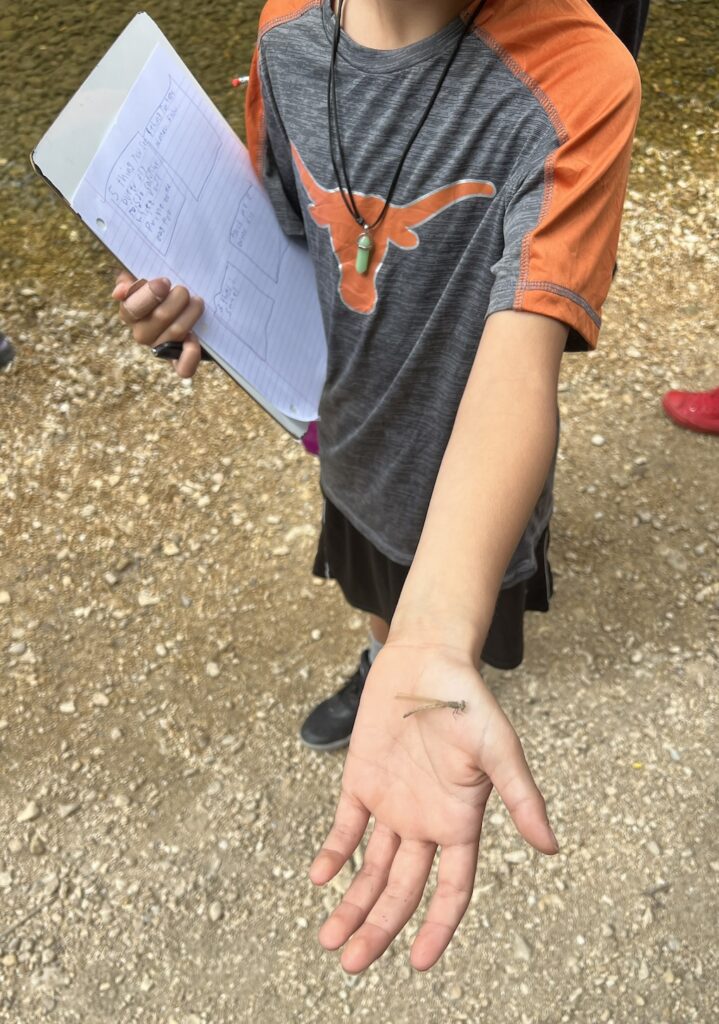

As we approached the end of the spring semester, we began to read several books by Indigenous authors. One theme that emerged was the importance of elders in the community as those who teach others about the knowledge held by the Earth. We read Berry Song by Michaela Goade and discussed the importance of taking care of the earth, as it is the earth who takes care of us. We identified the native plants around our community as vital to the ecosystems that already exist there. When we planned our walk to the creek, we discussed what our role was in the ecosystem: we are learners observing our surroundings and making connections with what we already know. Students prepared a paper divided into quadrants labeled: four things I can see, three things I can hear, two things I can smell, one thing I can touch. Students took notes on the things they observed in the environment.

Connecting with Our Land

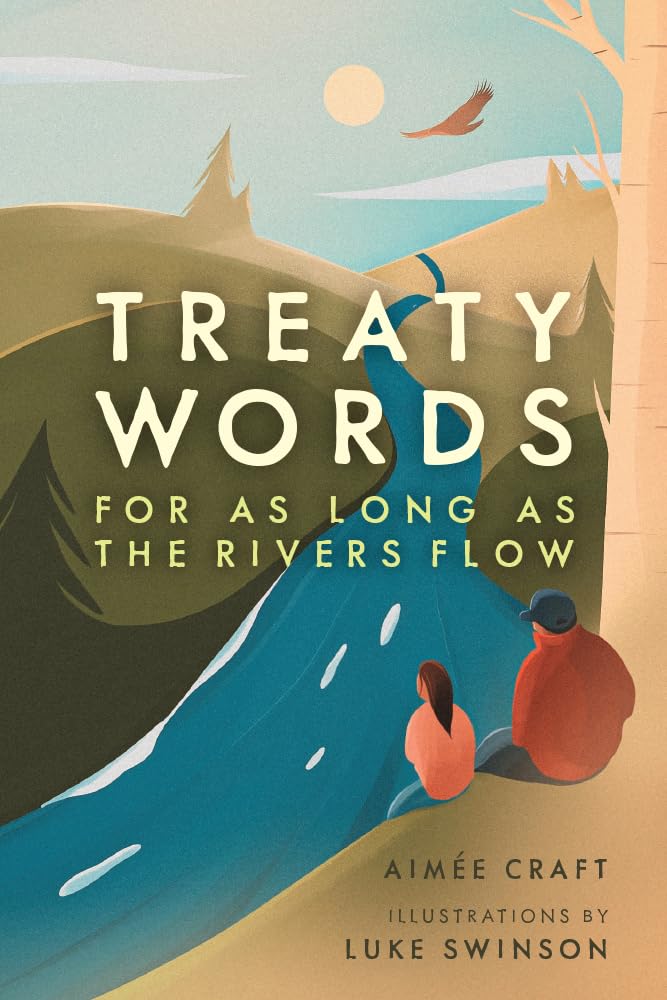

Throughout the year, we had identified the colonization of land through various social studies lessons. When we arrived at the creek, we formed a circle and read a couple pages of Treaty Words: For as Long as the Rivers Flow by Aimeé Craft. We discussed how land and water have been historically claimed by non-Indigenous people, how wars have been fought and treaties have been made on the account of ownership of land and water. We talked about how water and land hold memories, how they represent the histories of the people who have lived there for many generations. It was here that students began to tell me about their stories and memories. Our community experienced devastating flooding in 2013 and 2015. Although most of my students were too young to remember, many of them had older siblings or parents who recounted having to get evacuated from the neighborhood due to the floods. Other students talked about their immigration journey, one in particular recounted how he remembers crossing the Rio Grande on his father’s back. We made connections with the land and the water around us—not as owners but as active participants of an already thriving ecosystem.

To finish out our unit, students took time making a collective writing project of all the things we had learned from our walk. Some students made connections to their science lessons and talked about weathering, erosion, and the organisms they had seen. Others drew about the personal connections they had to the land and the water. The goal of this unit is to position students as experts in what they already know, with the teacher facilitating discussion and guiding thinking through literature. Students finished the unit as advocates and activists of the land and water that surrounds our community, feeling confident in their own ideas and eager to share their histories with others.

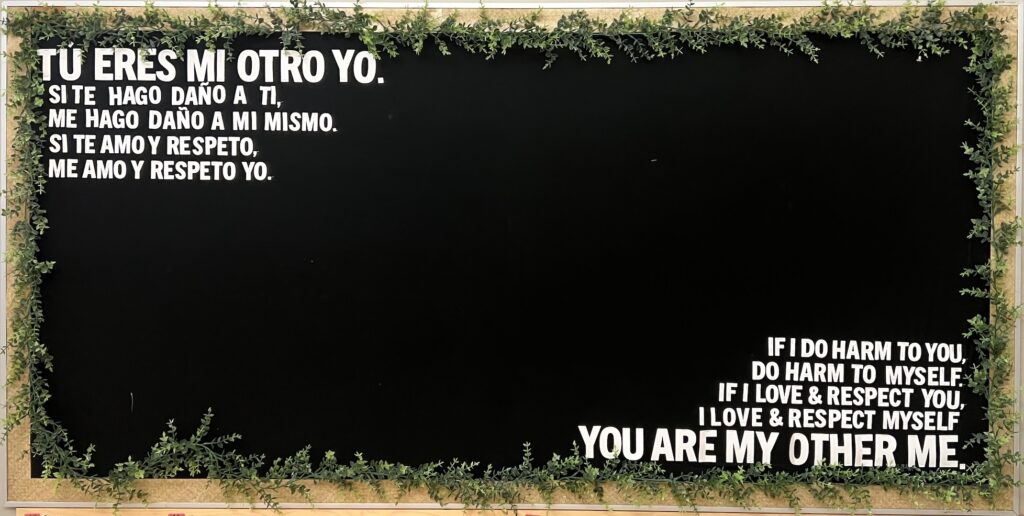

Two years later, what I learned from this group of kids stays with me. When my current students leave pencils on the ground or break a pair of scissors, we sit around the carpet and discuss the raw materials used to make their tools. We talk about the trees, that they have to be killed in order to harvest the wood used to make pencils. That the wood has to be transported and treated in a facility that pollutes the air and water, and that the finished product travels miles to get to the grocery store in order to make it to their hands. We discuss the importance of taking care of our materials as a way of taking care of the earth, that as consumers we are partially responsible for ensuring that our home is well taken care of. Outside of my classroom is the poem “In Lak’ech” by Luis Valdez (1971). It reminds us that the earth is our other self, when we take care of it, it in turn takes care of us.

Recommendations for Educators

- Learn who the Indigenous people in your area are.

- Bring in literature that is relevant to the land and green spaces around your community.

- Encourage students to lead discussions with open ended questions and accountable-talk stems.

- Pose students as experts by having them share their own stories and memories in connection to the land.

- Lean into activism as the product of a unit.

Other Book Recommendations

from https://bit.ly/NativeWaysofKnowingBooks

- This Land: The History of the Land We’re On by Ashley Fairbanks

- Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Golda Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer by Traci Sorell

- All Around Us by Xelena González

- Remember by Joy Harjo

References

- Valdez, C. (2020). Flippin’ the scripted curriculum: Ethnic studies inquiry in elementary education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 23(4), 581–597.

- Valdez, L. (1971). I am you or you are me / In Lak’ech. Retrieved from https://www.teachingcentralamerica.org/in-lakech.

- IndigenousCultures.org. (n.d.) Indigenous Cultures Institute.