With more than two decades of teaching experience, I know that assessment is far more than scoring, testing, or ticking boxes. Thoughtfully observing children’s reading, writing, speaking, and listening helps me plan instruction that meets their needs, notice who may require extra support, and ensure no child is overlooked. Shared assessment language across grade levels strengthens communication with families and the school community, while also helping me reflect on my practice so it remains responsive and inclusive.

In this piece, I share how assessment unfolds in my classroom each day—through small moments, meaningful conversations, student choices, and authentic work—and how these practices help me truly see my learners and support their growth as readers, writers, speakers, and listeners.

Seeing Children through Assessment

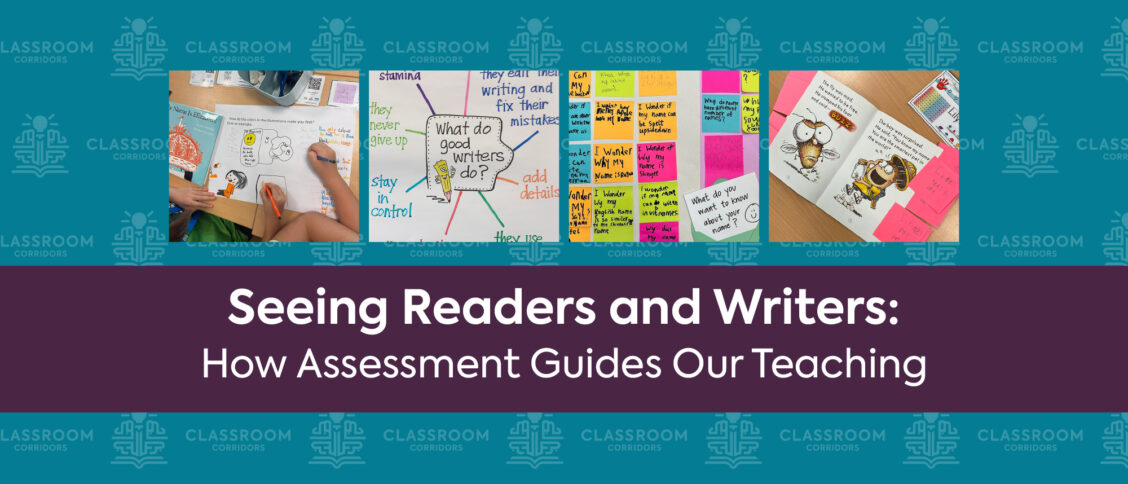

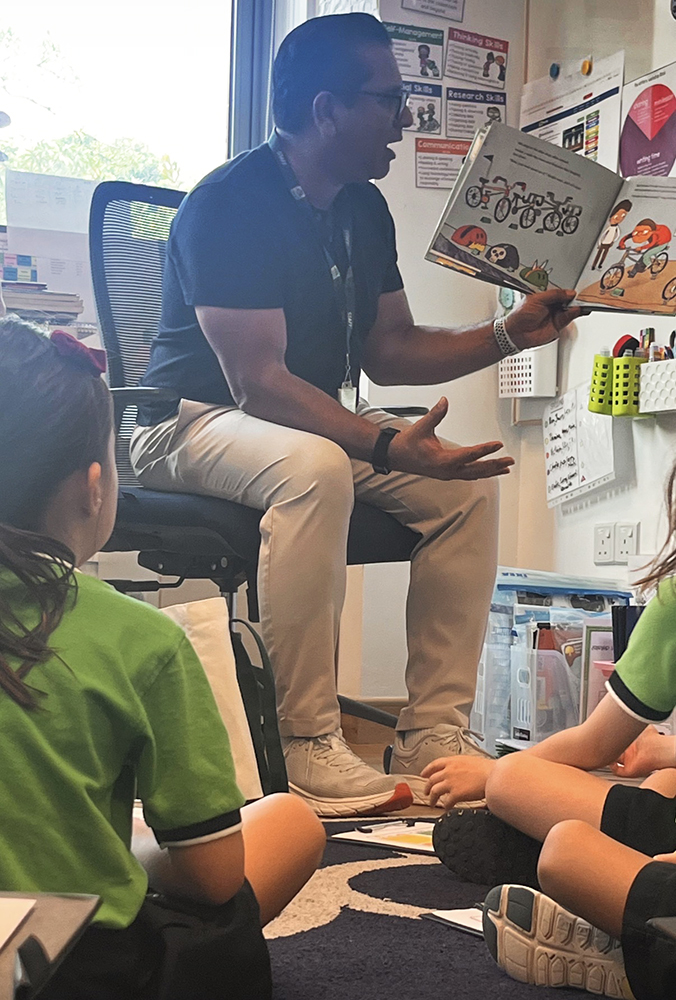

Assessment is a way of seeing children. Daily reading and writing practices reveal students’ thinking, conversations clarify their intentions, and authentic work guides my teaching decisions. Each morning, as students settle with books, jot ideas, sketch stories, or share thoughts with partners, these moments become natural assessments. They show how children comprehend texts, use strategies, and make meaning across reading, writing, speaking, and listening.

In this essay I will share everyday snapshots that help me identify who needs support, who is ready for new challenges, and how to plan next steps.

Assessment in the Everyday Moments

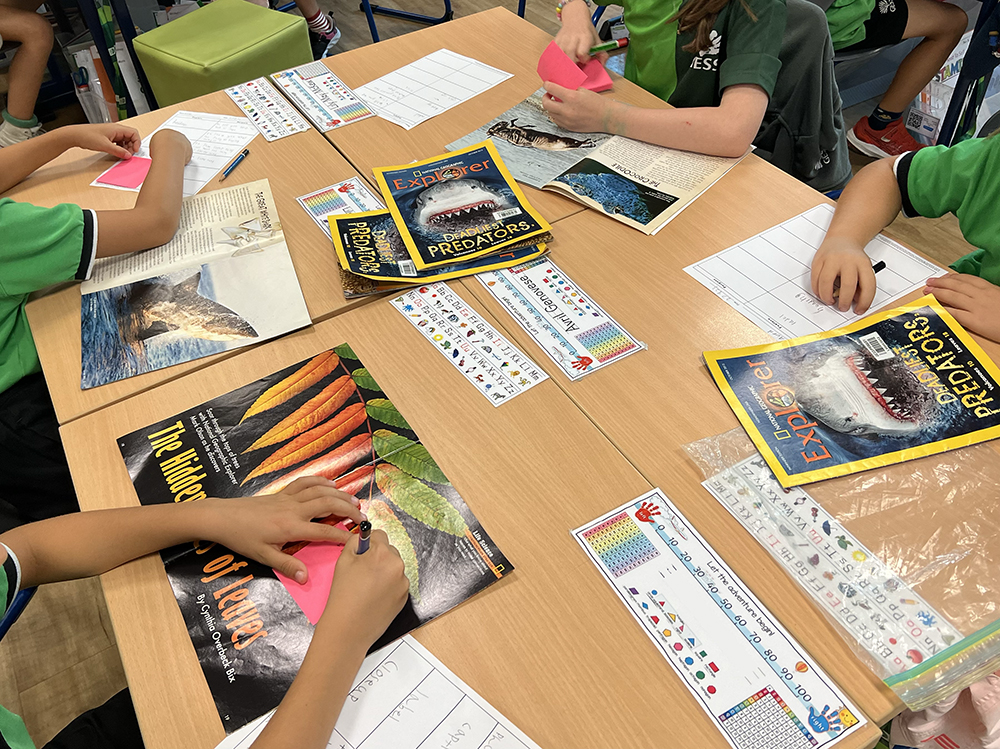

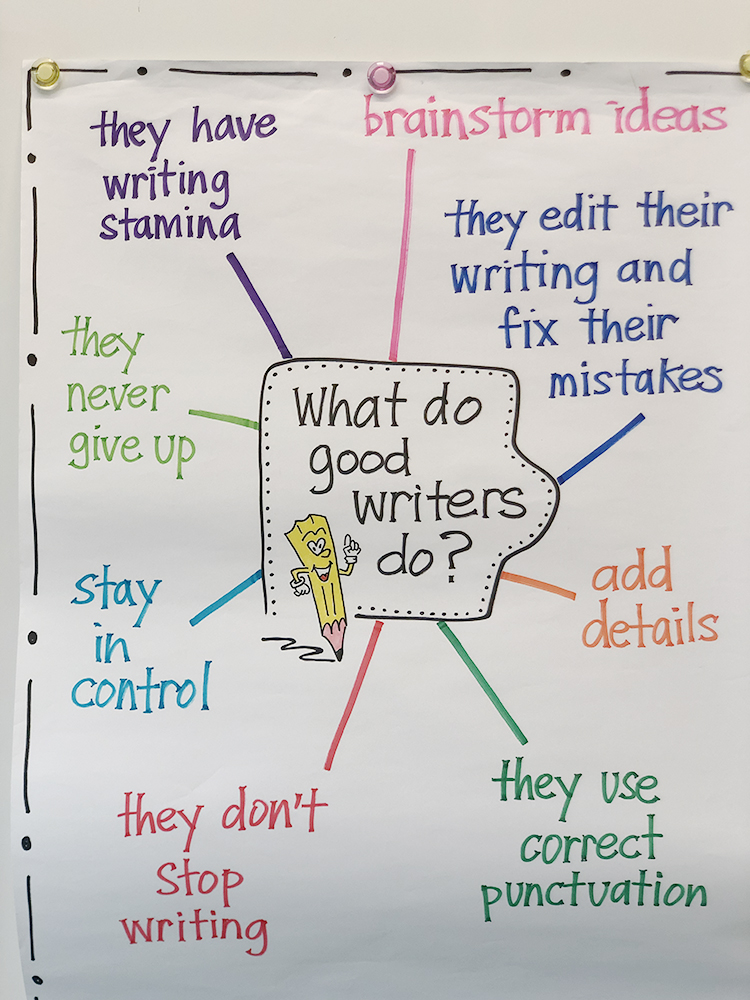

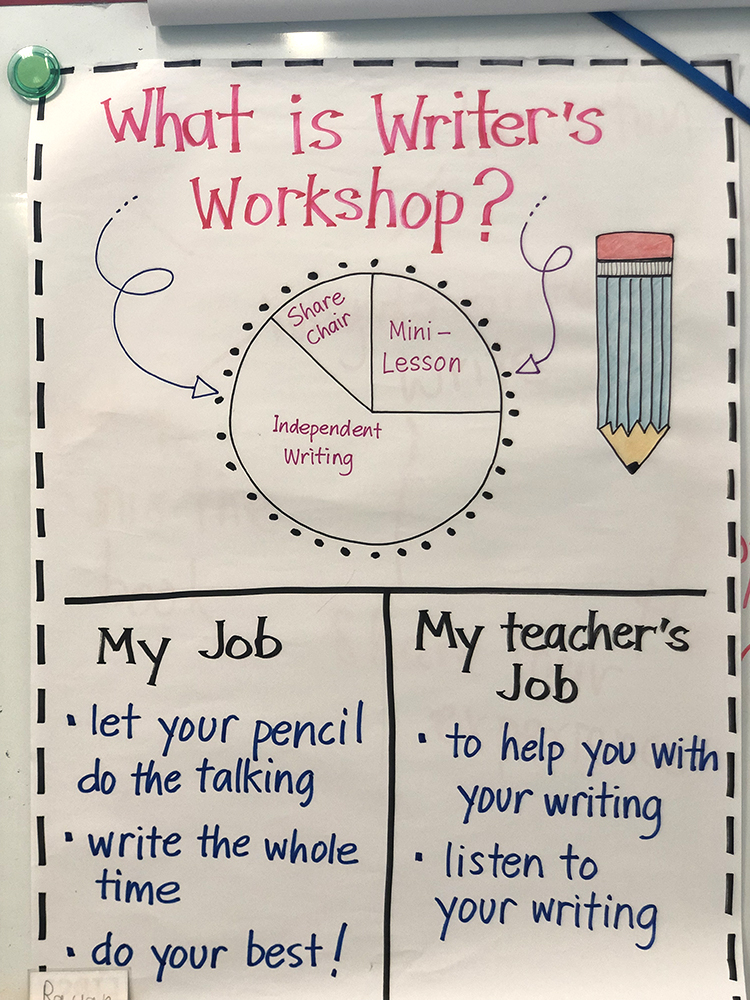

My understanding of workshop teaching began with Lucy Calkins (1994) and deepened through the work of Donald Murray (1972) and Donald Graves (1983), who emphasized process, choice, and authentic writing. My workshop rests on access, choice, response, volume, time, and ownership. Children need rich texts, meaningful options, and daily opportunities to read and write deeply. Their choices, conversations, and work reveal who they are as learners, making assessment continuous and embedded in their daily experiences (Goudvis et al., 2019).

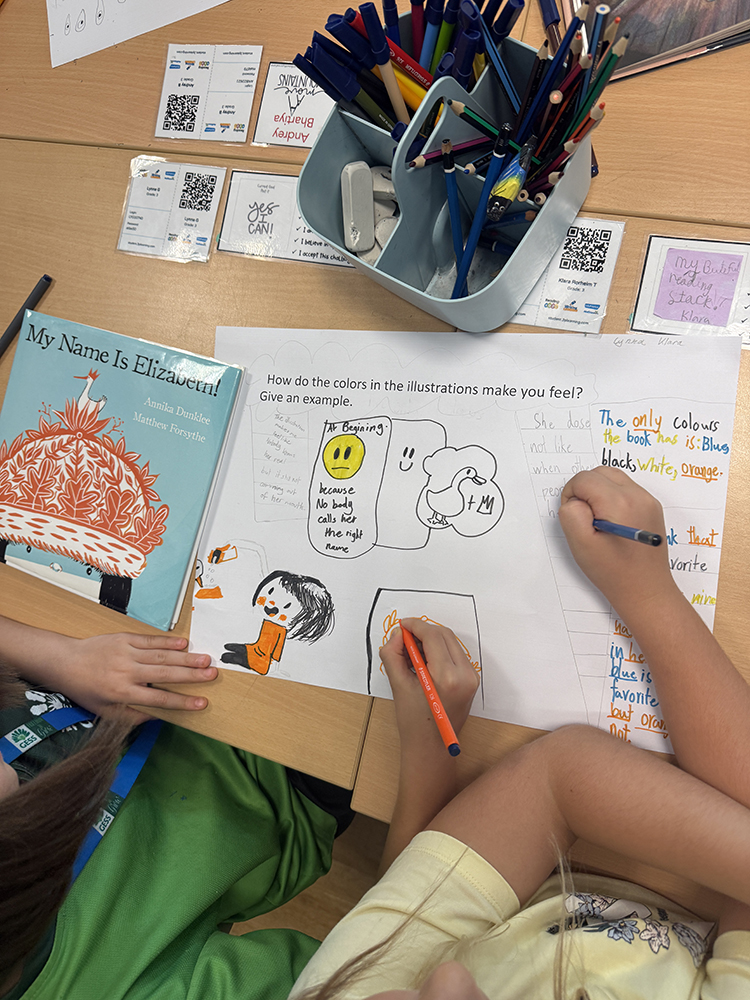

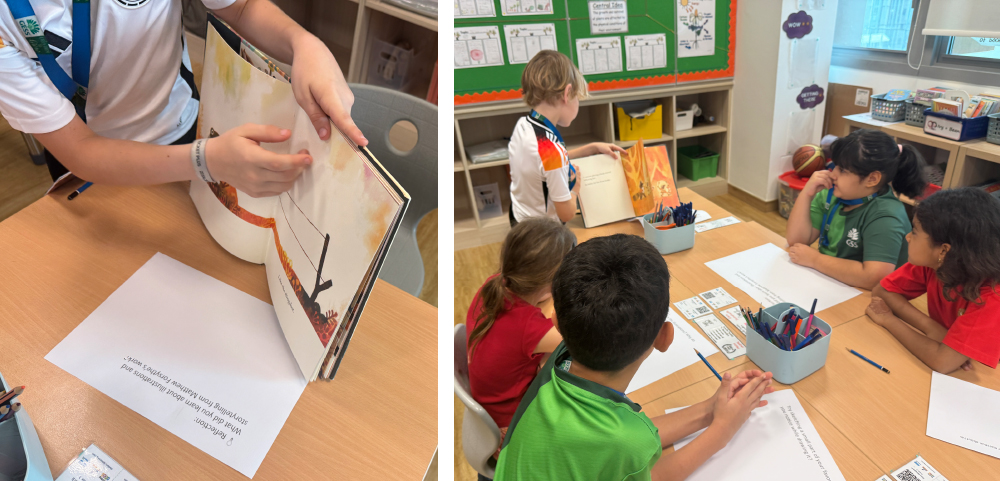

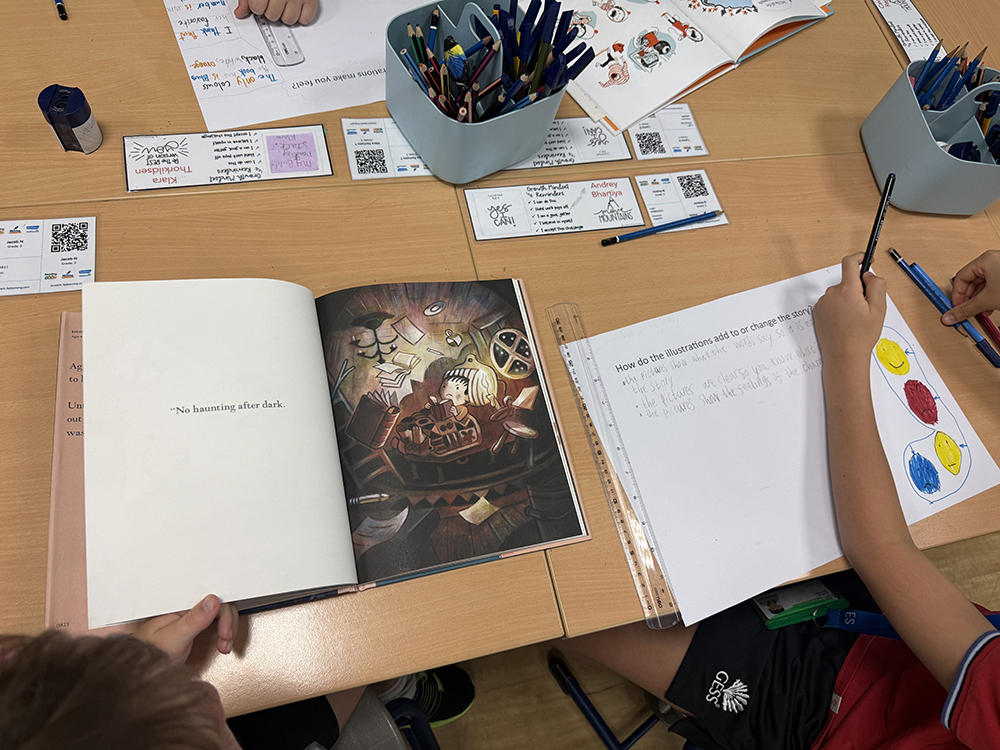

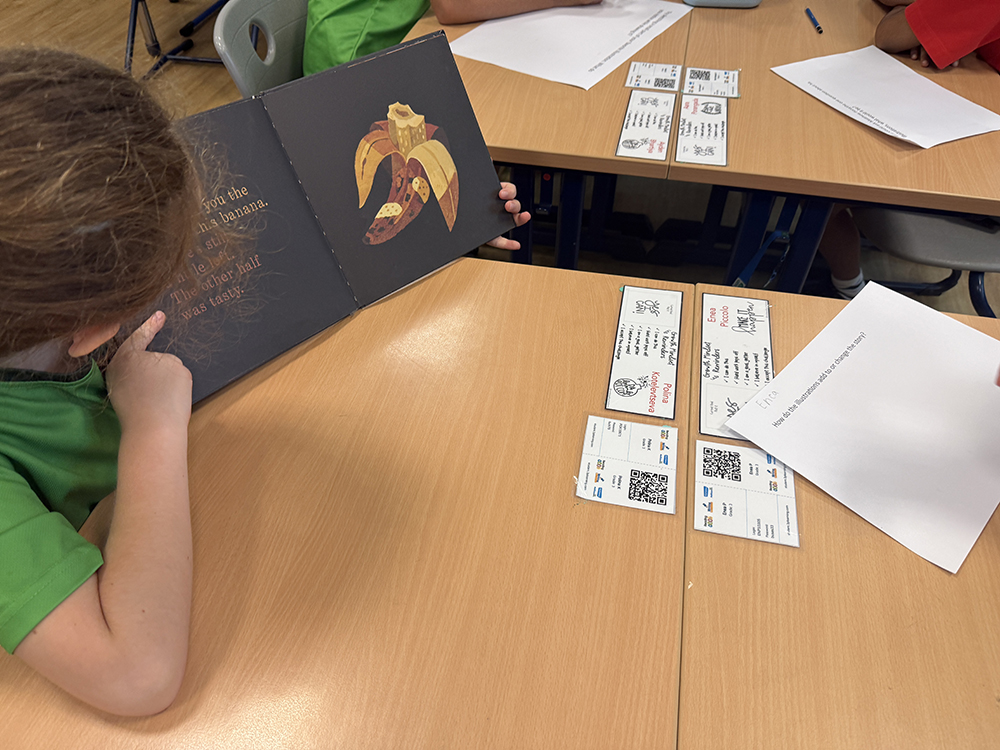

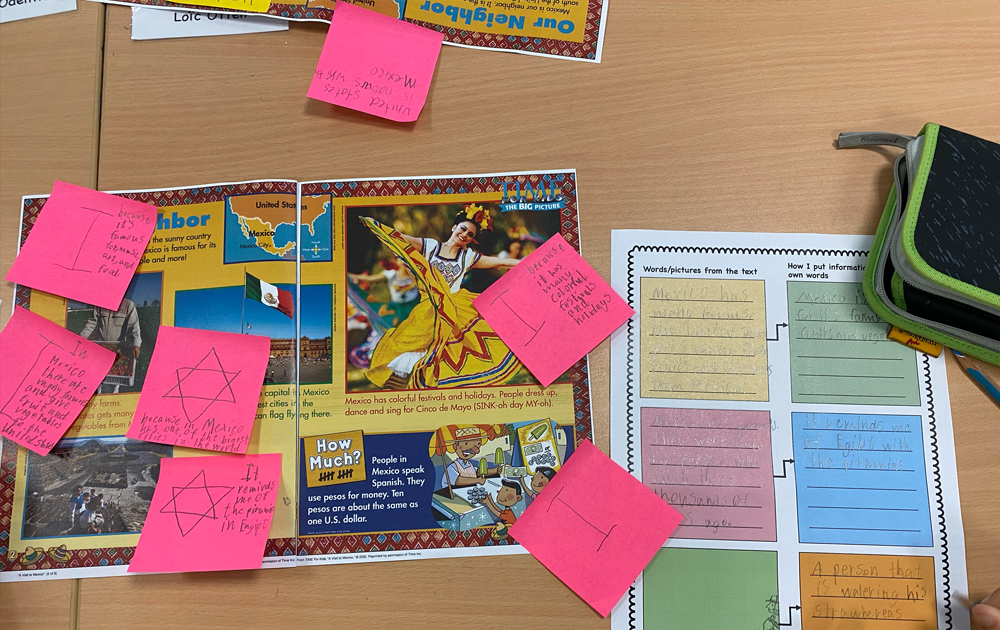

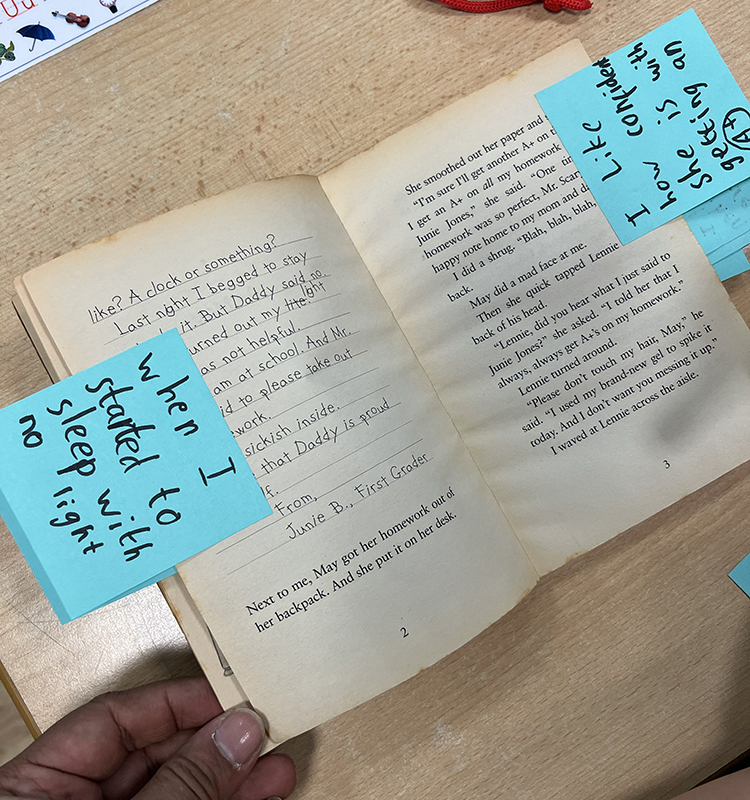

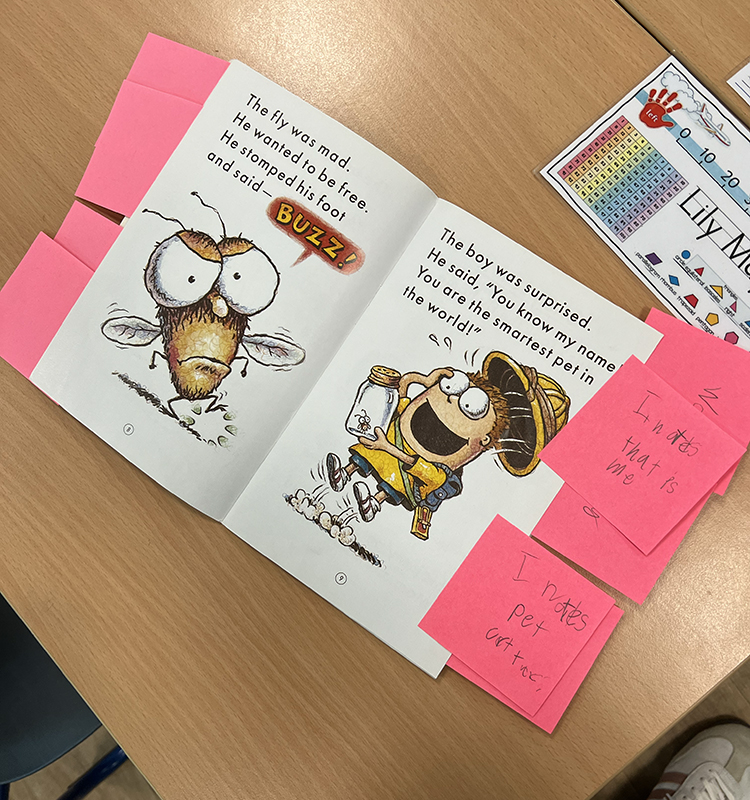

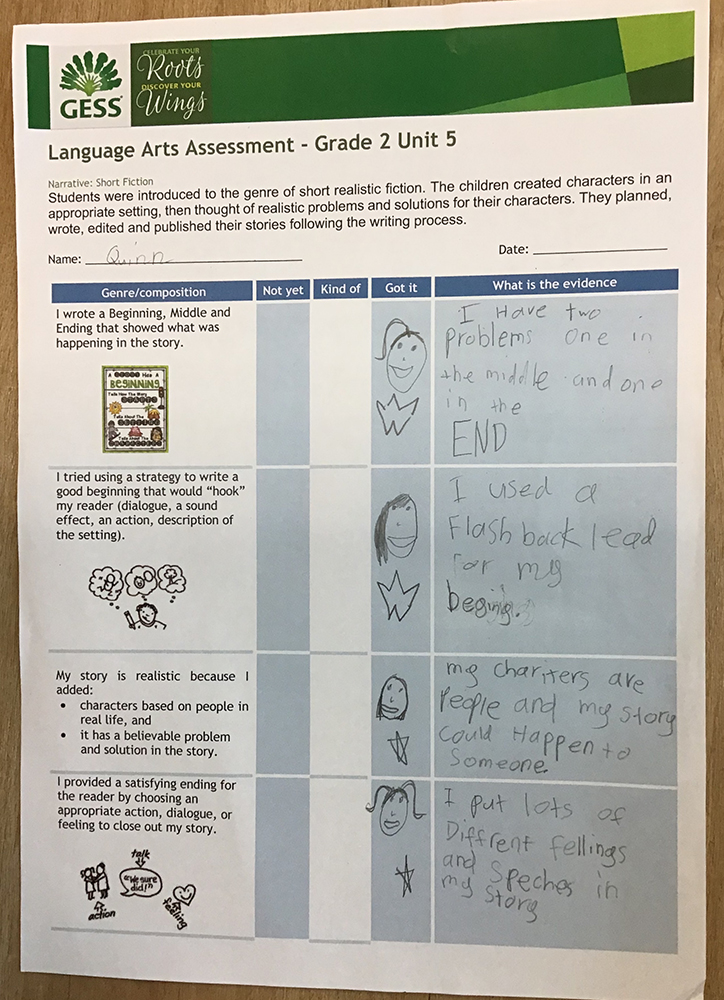

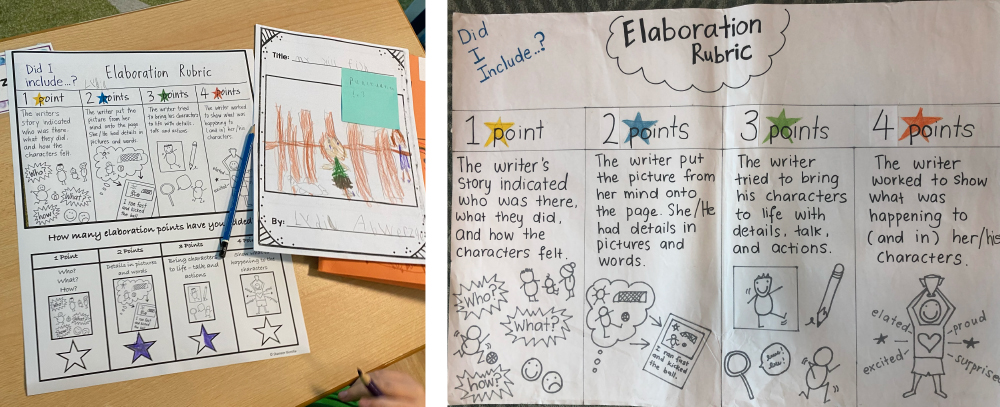

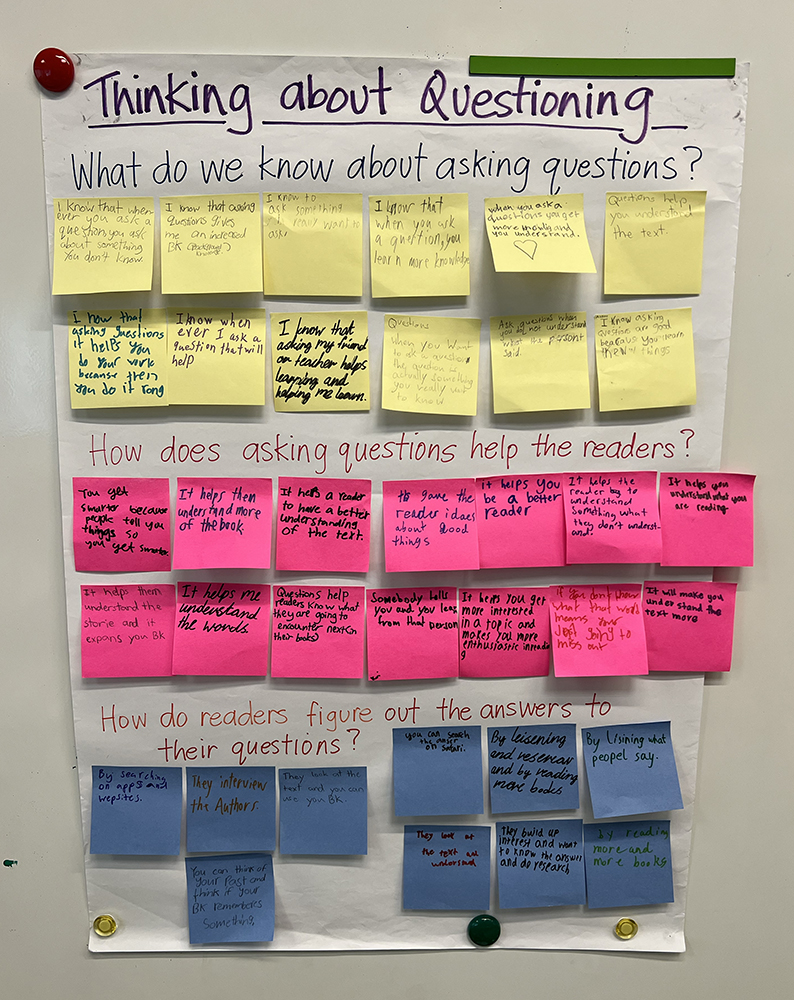

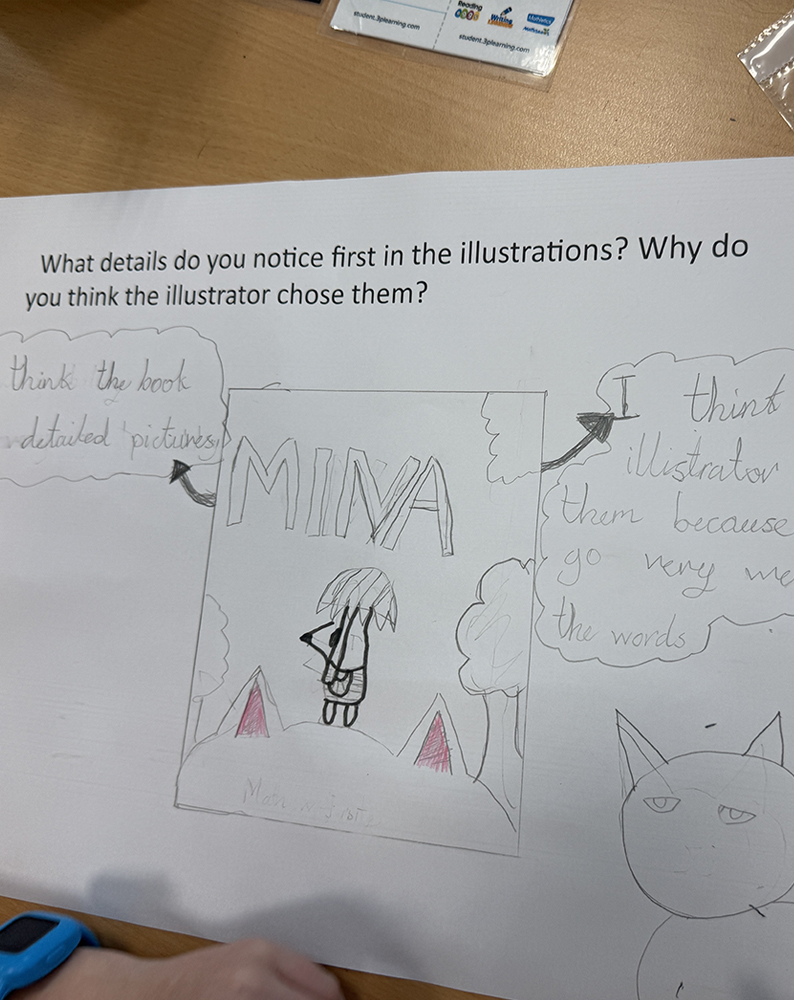

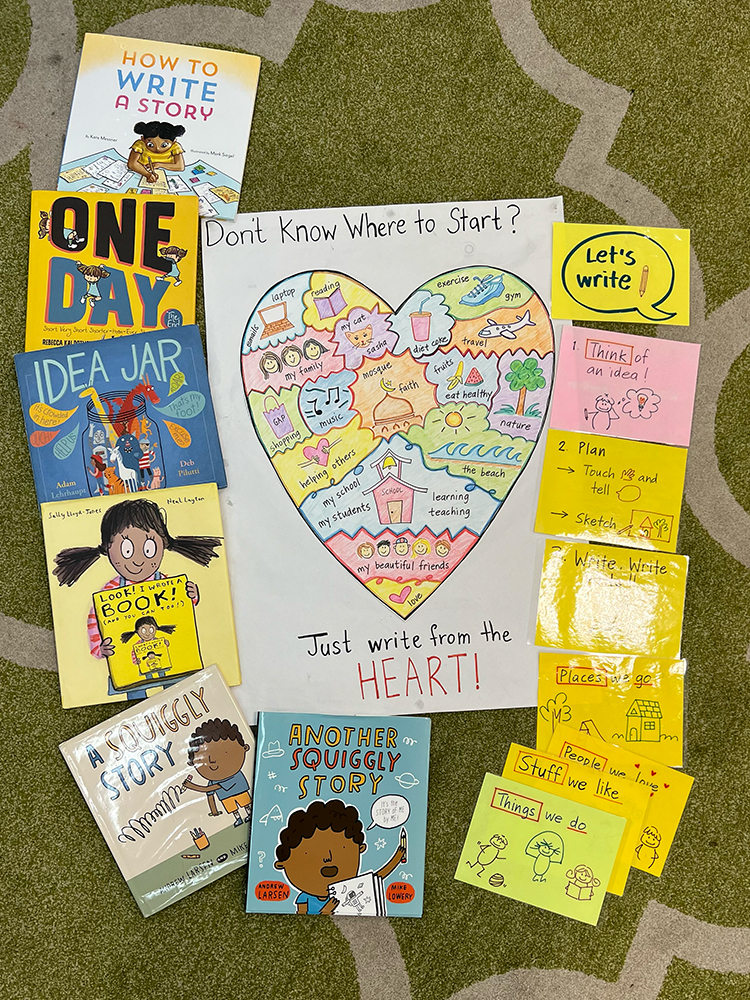

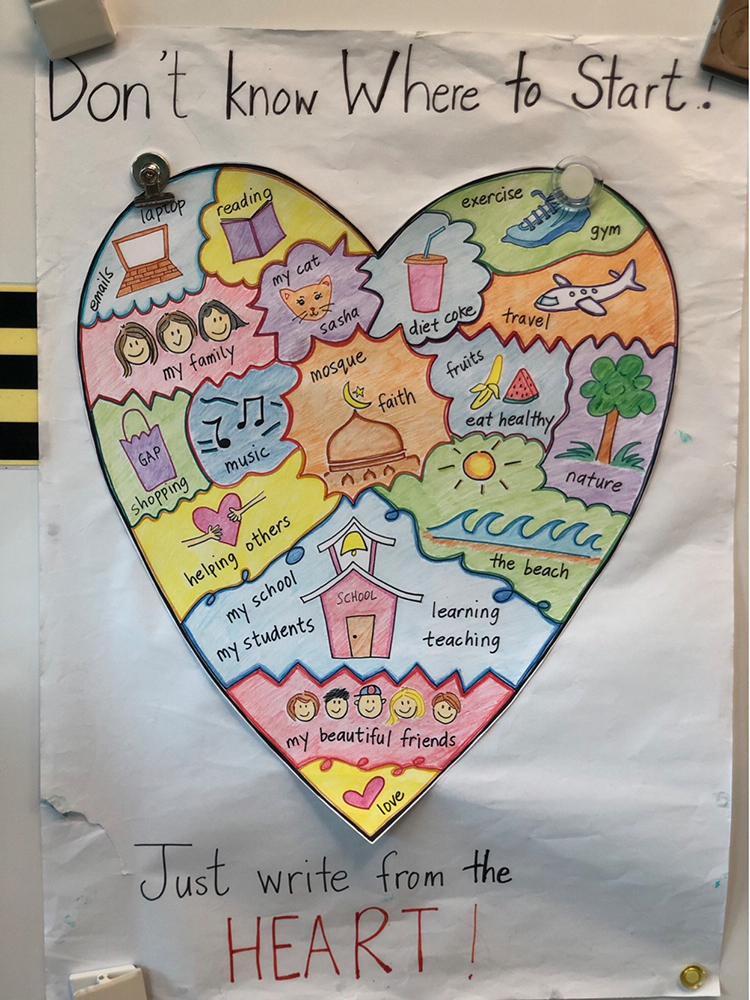

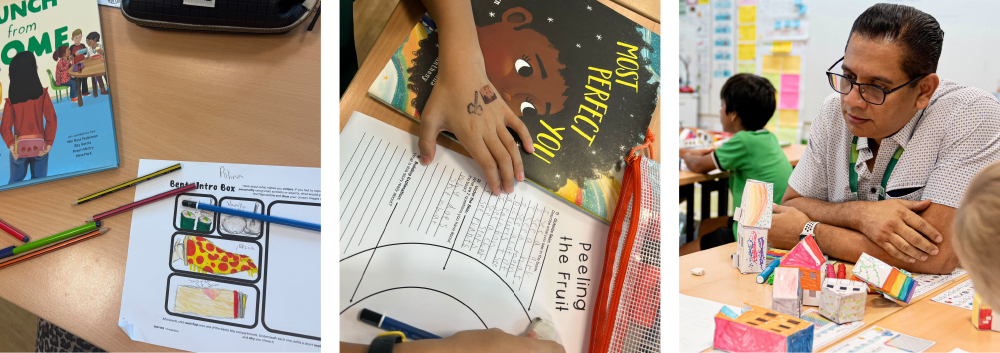

The images in this section highlight the assessment in everyday moments that guides my instructional decisions.

How Formative and Summative Assessment Work Together

Assessment helps me understand my students as learners. As Tomlinson (2014) notes, ongoing assessment provides teachers with daily information about children’s readiness, interests, and learning profiles. Observing students’ talk and work shows who understands our big ideas, who needs more time, and who is ready to stretch. These insights shape my next lessons—sometimes the same day.

Assessment takes many forms: small group conferring, one-on-one conversations, whole group sharing, noticing something in a child’s writing, or reviewing interest surveys. Summative assessments complement this daily noticing by showing how students have grown over time.

Together, they create an honest, accurate picture of each learner.

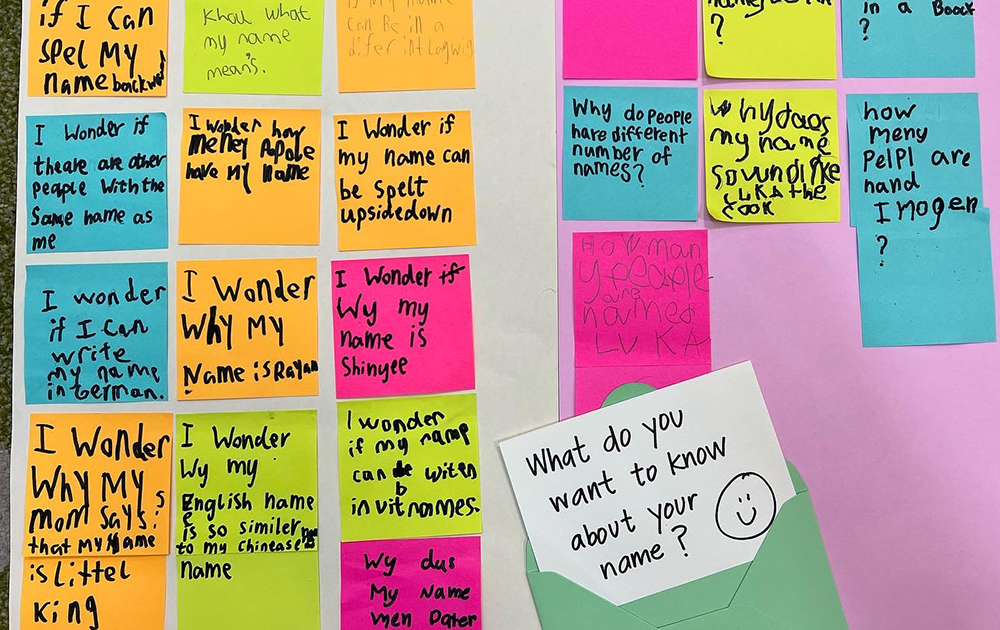

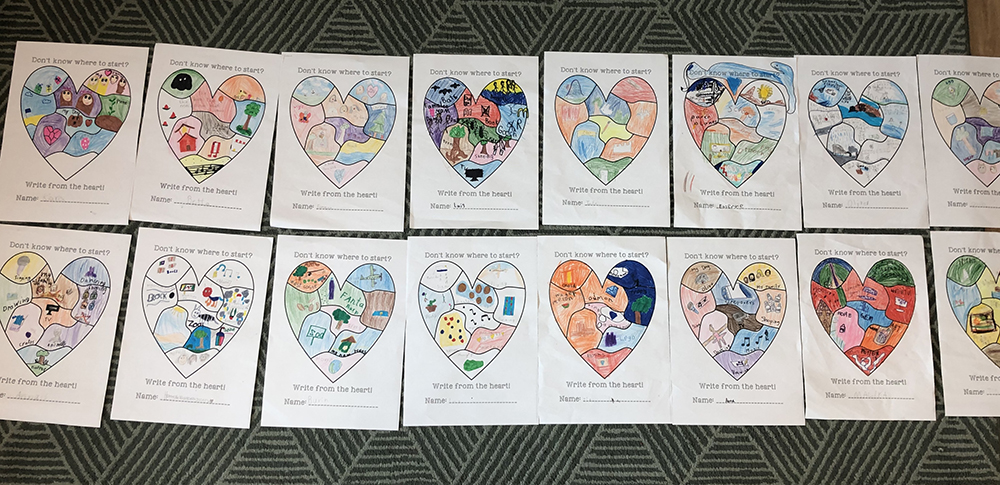

Student Voice and Choice as Assessment in Writing

Heart Maps, inspired by Georgia Heard (1999), help me learn about my writers. After I model my own map, students fill theirs with people, places, memories, and moments that matter. These choices reveal early writing identities—what students care about, what feels safe, and where they need support. This aligns with Atwell’s (2002) emphasis on authentic choice, Johnston’s (2004) view of identity in literacy, and Miller’s (2009) reminder that children’s choices show who they are becoming. Research also shows that choice increases engagement and independence (Gambrell, 2011; Ivey & Johnston, 2013).

Heart Maps become both a poetic tool and a formative assessment that guides responsive instruction.

Heart map anchor charts invite students to choose topics that matter to them, making their interests, experiences, and writing identities visible. These choices provide formative assessment information about what students value, how they generate ideas, and where they may need support as writers.

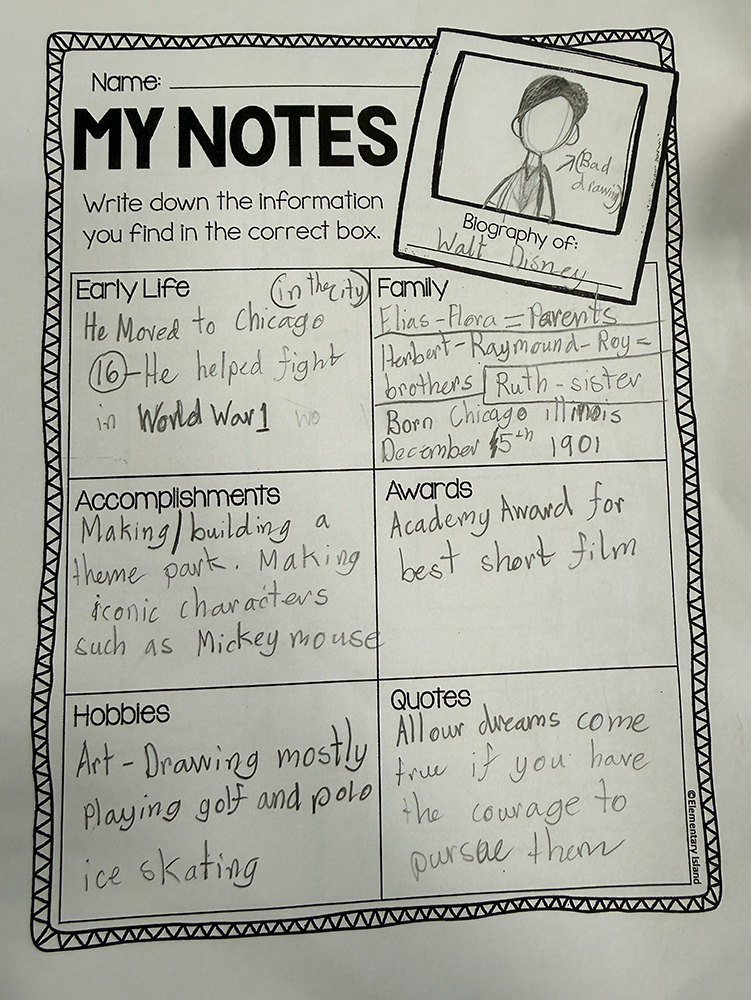

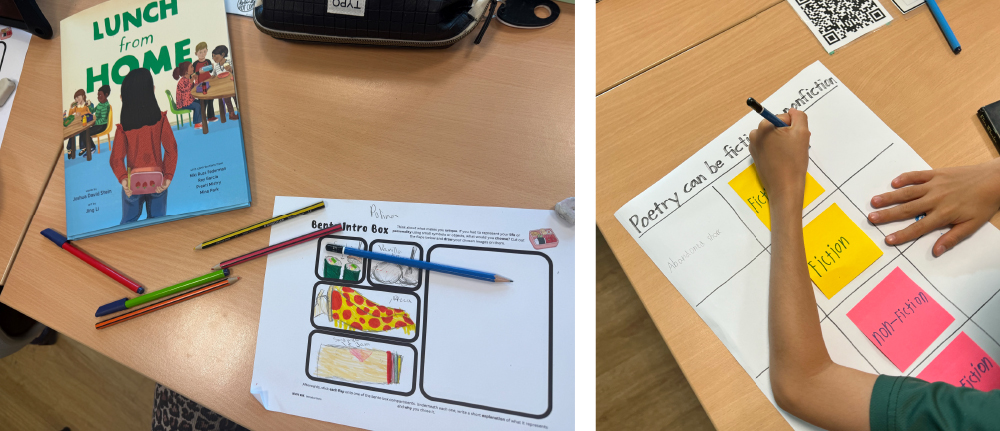

Student Work as Windows into Learning

Student work provides some of the richest assessment information. Graphic organizers and planning sheets reveal early thinking and the strategies students use to organize ideas (Calkins, 1994; Graves, 1983). Drafts and revisions show how writers take risks and strengthen their craft. Reading jots and sticky notes reveals how students make meaning as readers and which strategies they use independently (Serravallo, 2019). Published pieces offer a summative snapshot of what students can do on their own.

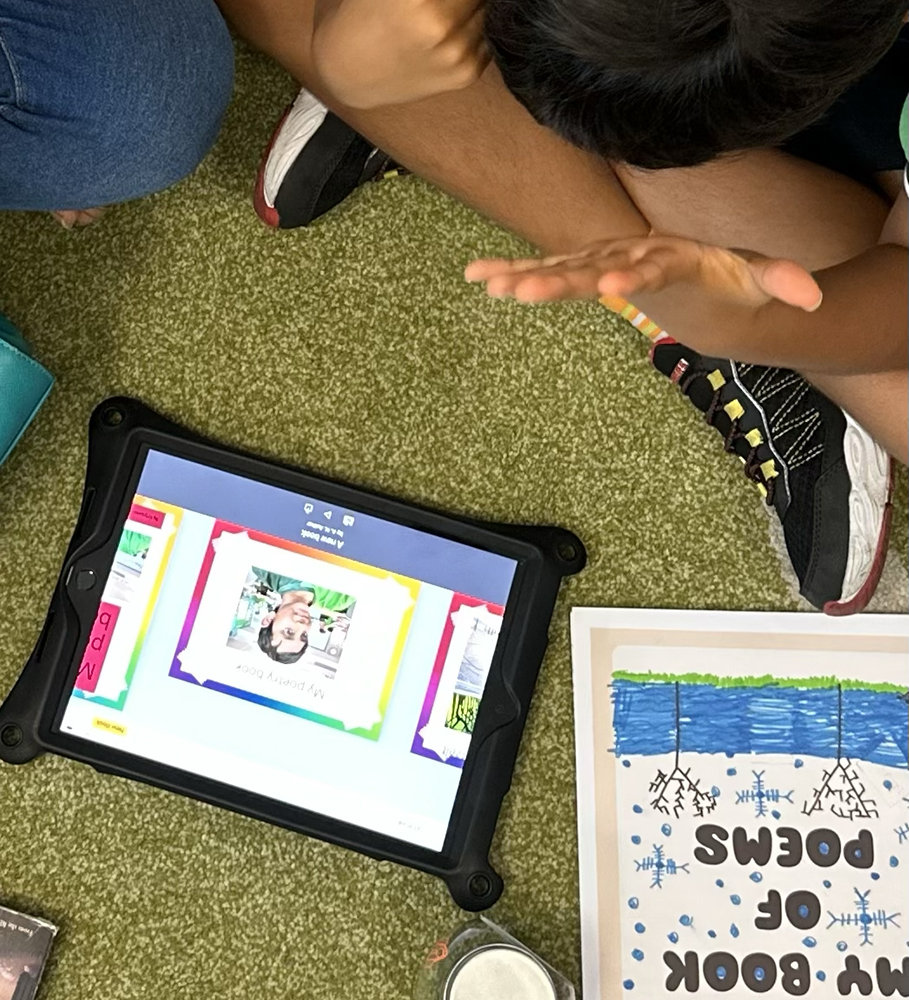

At the end of a unit, students compile their work in Book Creator, adding reflections and process photos. These digital summative assessments highlight their thinking, choices, and growth. When students share their projects with peers or families, their pride becomes a powerful form of assessment.

Together, these pieces—informal and formal, formative and summative—serve as windows into students’ thinking and guide every instructional decision (Johnston, 2004).

After reading, students record their understanding by sorting information into a bento box organizer, making their thinking visible. In the poetry task, students demonstrate their understanding by identifying and categorizing features of poetry. Together, these pieces of student work provide a window into how learners comprehend texts, organize ideas, and apply concepts.

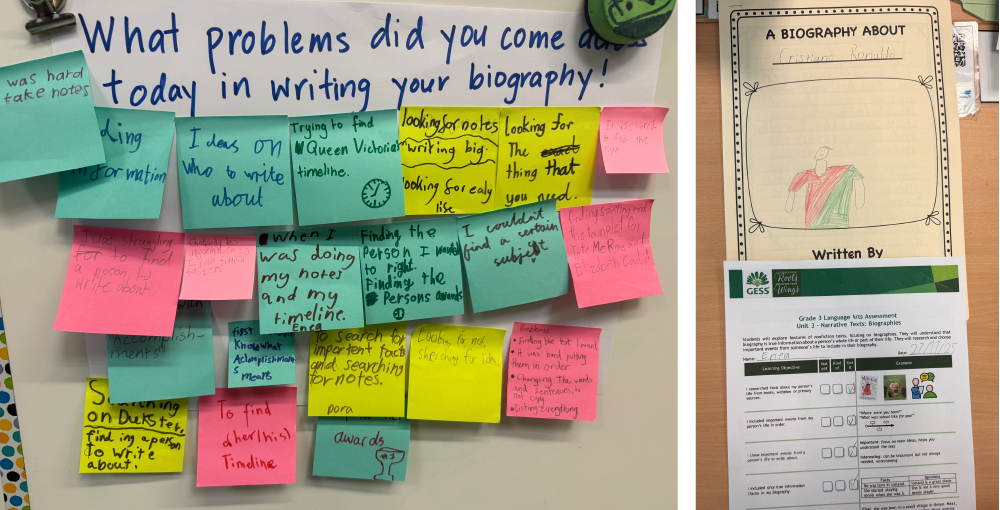

The pre-assessment activity captures students’ existing knowledge and questions about biography writing, making their thinking visible before instruction begins. The completed biography, assessed by both student and teacher, serves as a summative assessment that reflects growth in understanding, writing craft, and application of learning. Together, these pieces of student work offer a window into learning across the writing process.

During the writing celebration, students share their digital portfolios created in Book Creator, where their poetry is drafted, revised, and published. These portfolios serve as a summative assessment, capturing students’ writing processes, choices, and growth over time. As students present and reflect on their work, the published pieces provide a clear window into their development as writers.

Feedback as Assessment and Assessment as Feedback

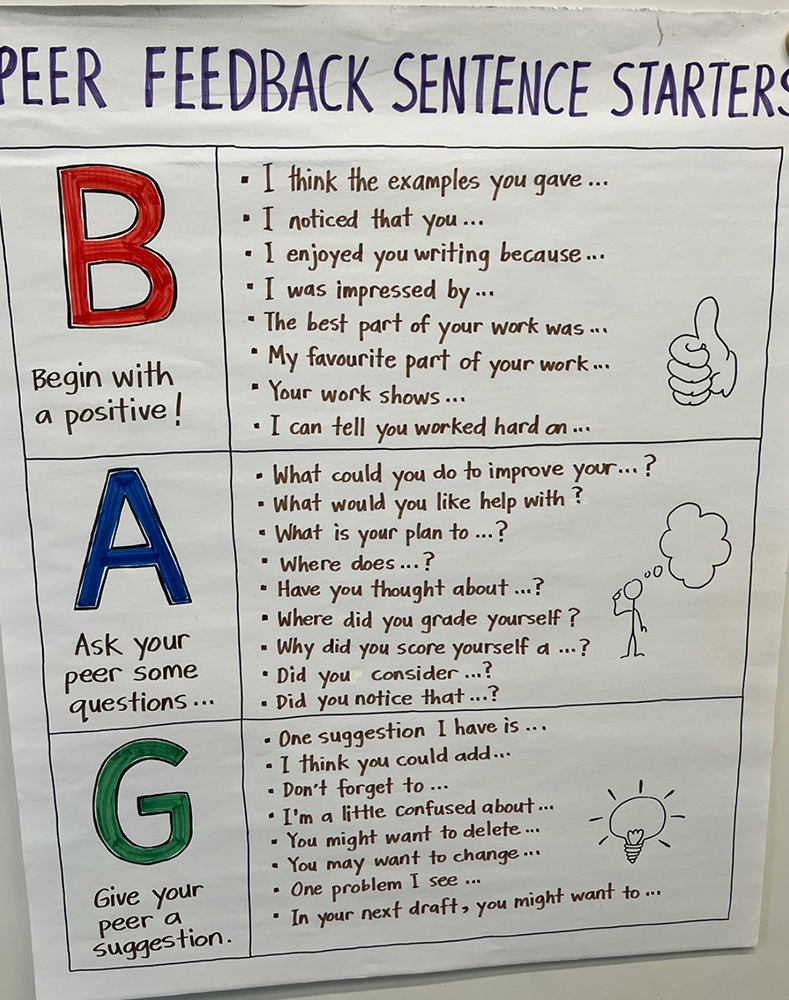

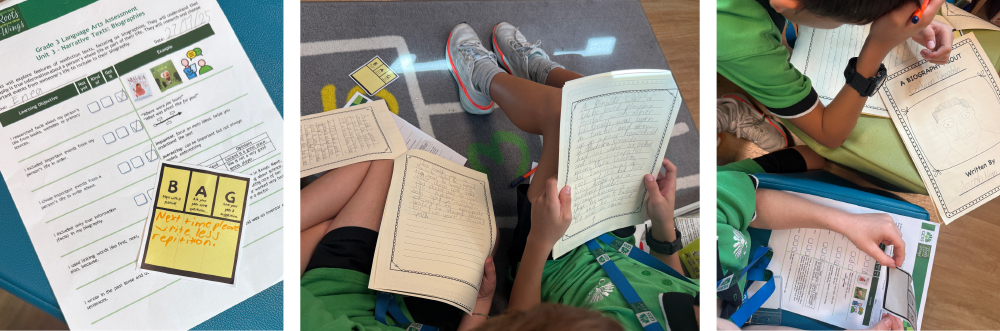

Feedback is woven throughout our literacy classroom. In conferences, I name a strength and offer a teaching point students can try immediately. Anderson (2000) reminds us that we always have opportunities to confer. Students also use our B.A.G. routine—Begin with a compliment, Ask a question, Give a suggestion—to support one another. Peer feedback reveals how students reason and which strategies they are trying.

Teacher conferring, peer responses, family comments, all those feed into my summative assessment. When I use a rubric to evaluate published pieces, that judgment reflects weeks of daily noticing, conference notes, and student self-assessment. Hattie and Timperly’s (2007) research shows that feedback has one of the greatest effects on learning when tied to clear goals. Summative assessments mean more when they grow out of formative practices that value the whole child (Serravallo, 2015).

Feedback and assessment are inseparable. Because formative learning is ongoing, summative assessments become fair, thoughtful, and centered on the child.

Students engage in peer assessment using the B.A.G. routine—Begin with a compliment, Ask a question, and Give a suggestion—while reading and responding to one another’s writing. As students listen, reflect, and revise based on peer feedback, assessment becomes a shared process rather than a final judgment. These moments allow both students and teacher to gather meaningful assessment information about writing strengths, next steps, and growth.

Putting It All Together: A Child-Centered Assessment Lens

Assessment begins and ends with the child. Daily observations, quiet conversations, peer interactions, and family feedback help me understand who each learner is and who they are becoming. These moments shape tomorrow’s lessons—and often today’s.

By the time we reach a summative assessment, it reflects everything the student has learned, the feedback they have received, and the growth they have experienced. Assessment should never rank or label children. It should honor their identities, acknowledge their progress, and ensure that every learner is seen, supported, and valued.

References

Anderson, C. (2000). How’s it going? A practical guide to conferring with student writers. Heinemann.

Atwell, N. (2002). Lessons that change writers. Boynton/Cook.

Calkins, L. M. (1994). The art of teaching writing (2nd ed.). Heinemann.

Gambrell, L. B. (2011). Seven rules of engagement. The Reading Teacher, 65(3), 172–178.

Goudvis, A., Harvey, S., & Buhrow, B. (2019). Inquiry illuminated: Researcher’s workshop across the curriculum. Heinemann.

Graves, D. (1983). Writing: Teachers & children at work. (Heinemann).

Heard, G. (1999). Awakening the heart: Exploring poetry in elementary and middle school. Heinemann.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Ivey, G., & Johnston, P. (2013). Engagement with young adult literature. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(3), 255–275.

Johnston, P. H. (2004). Choice words: How our language affects children’s learning. Stenhouse.

Miller, D. (2009). The book whisperer: Awakening the inner reader in every child. Jossey-Bass.

Murray, D. M. (1972). Teach writing as a process, not product. The Leaflet, 71(3), 11–15.

Serravallo, J. (2015). The reading strategies book: Your everything guide to developing skilled readers. Heinemann.

Serravallo, J. (2019). A teacher’s guide to reading conferences (Classroom Essentials). Heinemann.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). ASCD.

Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Solution Tree Press.