This piece is written by three early childhood educators. We came together over social media many years ago and have developed a friendship and space to share and unpack educational and social issues impacting children and our communities. We presented together at the Reading for the Love of It conference in Toronto in 2025, and we continue to engage in conversation and questioning of our pedagogy.

Katie Keier

We invite you to enter into our piece by considering your image of the child. Our image of the child is such that children are citizens—as they are right now, as five-, six-, eight- or ten-year-olds—and they have rights and an equal say in our classroom community. They are made up of many stories. We approach them with the belief that they are competent and capable and that they have strong voices and brilliant ways of thinking. We create our community together, through listening and sharing our stories. Connecting and honoring all voices in the classroom is key. It’s not about compliance or control. If we are approaching our classroom community with a belief that the adults make all the decisions, or that a curriculum is to be followed verbatim, we will struggle to create a safe and open space that is key to creating conditions for critical conversations and for joyful learning. We ask you to consider that operating from a place of control and compliance is a form of oppression. We risk silencing children, and it actually can become adultism—a bias or prejudice against children and young people. Think about the views children, even in the early years, have about rules and school. Many of them already have a view that school is about compliance, following the rules, and doing what the teacher says without any thought. What if we considered that control/compliance is a form of oppression? What if this approach shuts down children and silences the important stories they hold within? We invite you to think about your image or view of children as you build connections in your classroom. Are there any parts of the day when you are the only one in control, or when compliance is required? How can we rethink this? How can honoring children and their stories, listening to them, and viewing them as capable and competent make a difference in the classroom community and the learning that occurs there? Let’s hear some classroom stories from teachers who dream boldly about what is possible for children and learning.

Heather Olah

Children are unique and complex, and we need to honour all that they bring to our spaces. My pedagogy is grounded in this belief. If we, the educators, limit children to one learning context, then we are doing just that—limiting learning. By providing space for learning to occur in a variety of ways across an extended period of time, we can ensure children have the space and conditions they need for optimal learning. This can be achieved through a play-based learning environment—a child-centred approach where the classroom inspires engagement and wonder.

In my kindergarten classroom, we flow between explicit instruction and play. At the beginning of the year we explored the question “Who am I?” Our focused conversations during our multi-day read-aloud about our names provided me with insight about the children’s understanding, but as I read over my documentation, I knew the quotes from the children were only the tip of the iceberg. I placed other picturebooks around the room that were also about the importance of names, and immediately new learning started to emerge. For instance, my documentation showed one child using loose parts to spell his name in English and in Korean. He shared “I love my name in both languages. Maybe because both languages are me.” Another child built her name using wooden alphabet blocks and got to work writing her name story—which she asked to share with the class! Pairing multi-day read-alouds with similar books for children to explore at learning areas during play leads to new connections and deep thinking.

Just like we make intentional decisions about what texts we choose for our multi-day read alouds, we also make intentional decisions about what and where we place books in our learning areas: paired with loose parts, at the Art Studio, in the construction area, etc. The driving force behind these intentional choices is the children. As an active observer, kidwatcher, and documenter, I am positioning myself as a co-learner in the classroom. I listen to the children with an open heart and open mind and use my documentation to guide instructional moves. For example, after reading All Are Welcome by Alexandra Penfold, I noticed a group of children who often play at the construction area were quieter during our group conversations. The following week, I placed the book in the construction area. Immediately, I observed the very same children picking up the book and revisiting pages. They worked together to build a structure, and one child held All Are Welcome in her hands and said, “Every block has a place—it’s a community of blocks!”

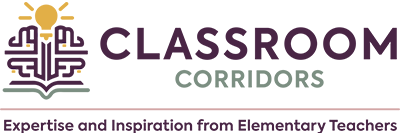

I continued to choose multi-day read-alouds around themes of identity and community, each time going deeper in conversations and providing more opportunities for children to strengthen their understanding through play. One day at the Art Studio, a child started to create what looked like people out of clay and carefully positioned them on a wooden board. He shared, “identity is also how people see you, remember like we talked about in the book Yo Soy Muslim?” He went on to explain, “people look at you and think things. Like here. These clay people might be thinking good things or mean things. How do we stop people from thinking the mean things?” Had I not continued to explore these important themes with the class, had I not prioritized play in the classroom, powerful questions such as this would be missed.

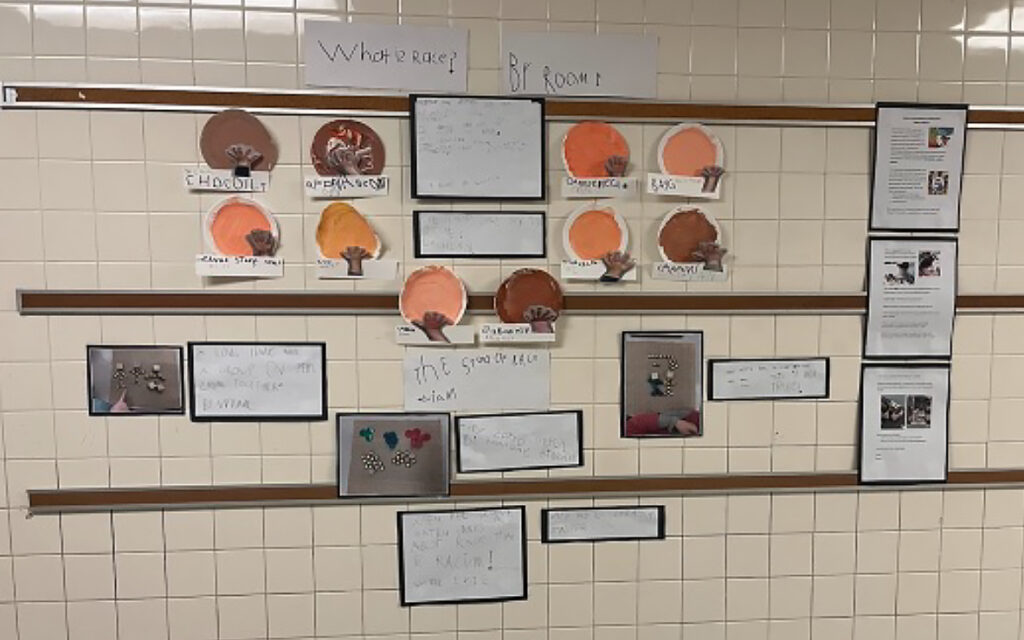

My creative, brave, and brilliant early years learners spent the year engaged in deep learning. They questioned, explored and taught others. They put up hallway displays to send important messages about race to the school community. They created videos to teach others about how to be an ally. They brought in books from home to spark new dialogue, more play, and rich learning. Each child is finding their own voice and is given the space to select the materials they would like to use to share what matters to them. And oh, what a privilege it is to be a part of this process—to dream boldly and bring this dream to life.

Nick Radia

My own story of coming to Canada as a refugee fleeing war has informed my practice as an educator and my pedagogy. I was an outgoing student in Kampala who was always ready to share my thoughts and ideas. But because of the trauma of war, fleeing my country, spending time in a refugee camp for months, bouncing around several schools in a short time, and then finally arriving in Canada, I became shy and introverted. No one asked me about my story. As a young adult, I realized how much it would have meant to me to have a teacher who just found a way to ask about my story, what I had seen or heard, what I came to believe. It would have prevented a lot of challenges I had to eventually deal with. Finding ways for students to share about themselves and their beliefs is an essential part of who I am as a teacher. It is also a part of good pedagogical practice. The power of stories matters because humans make meaning through stories.

When we have created a classroom climate of trust built on strong relationships, a climate of dialogue, and a space of culturally relevant (Gloria Ladson-Billings) and responsive pedagogy (Geneva Gay), as Katie and Heather describe, we will have built a space that allows for deep and meaningful conversations and communication. This communication will take many forms, including comments during large- and small-group discussions and during play, as well as conversations between students and between students and educators. The students will show their thinking as they draw, write, build, create, and talk. As we pay attention to these various forms of communication, we learn about the students’ beliefs, their questions, and their wonderings about themselves and the world around them.

This communication drives our next conversations, the books we read and discuss, and the activities and materials we present to further their communication. For us to educate boldly, we must follow the dreamers in our classrooms: our students. They will tell us what their interests, questions, and wonderings are. In some spaces, some of the books we read must convey multiple meanings and messages and must allow for myriad conversations. But we must always follow the lead of the meaning makers and the dreamers: our students.

The use of mentor texts is critical to create a culture of dialogue to further students’ thinking and communication. They are a powerful tool as provocations for big conversations. This is where I begin my story of being an educator of young students in Toronto, Canada, where I have been a kindergarten and an early years teacher for 26 years. This same story recurs every year with every new group of students.

As a teacher who is passionate about inquiry and emergent pedagogy, I often begin the year with the power of questions and wonderings. During a recent conversation about the importance of questions and the power of “Why?”, a student asked, “Why do we all have different colored skin?” I made note of the question and the following day read aloud the book All the Colors We Are: The Story of How We Get Our Skin Color by Katie Kissinger

Bisrat (all names are pseudonyms) was a five-year-old student in our kindergarten classroom. She was of Ethiopian origin, with curly black hair, brown eyes, and caramel colored brown skin. She was a confident, outgoing, social child with a large friend group. She often shared her opinions during any small- or large-group meetings and activities. She stated, “I know I have more melanin. I know my ancestors have dark skin. I wish I had peach skin. I wish I had yellow hair. I wish I had straight hair. I wish I had a name like Ella. I like that name better.” A handful of other students showed a thumbs-up, which was our classroom signal to convey agreement with what someone was saying. Another student showed rolling hands, which shows they want to add on to what is being said. They said, “My skin is dark and brown (a deep, chocolate colored South Asian brown). My mom says I have to stay out of the sun to look pretty.” Again, a few more thumbs up. At four and five years old, these students were communicating an internalised dislike of their own identities. Another stated, “I have light skin, so I’m beautiful.” More thumbs up. When the conditions have been created, similar beliefs about self-identity and the identity of others will always emerge during discussions about mentor texts, followed by listening to the students as they build, draw, and create. The instinct we have as educators is to disagree with these statements from students. To say they are wrong, explain that everyone is beautiful, or give our own opinions immediately. This move will shut down students from expressing their beliefs and negatively impact a culture of dialogue. This is not to say we do not ever intervene or disrupt, but we must be careful and intentional when that is necessary. I made a note of this statement as information to help inform my next steps and to keep in mind when choosing more books to read. Keep in mind that we are doing the work for the entire year.

This is just one conversation with one classroom and one set of students. But it is a conversation that happens every year, once the conditions have been created. It is also a reminder of my own beliefs that developed a few months after I came to Canada as a nine-year-old Brown student. What we do about these beliefs as educators makes a lifelong impact on students.

As educators, we know the importance of daily read-alouds. Intentional and thoughtful choices of these mentor texts and the important discussions that emerge from the students as they are facilitated by the educators allow for more conscious, positive, and critically informed understandings of self-identity and the identity of others. In response to what Bisrat and the other students had communicated, I chose my mentor texts carefully throughout the year, I reached out to critical friends, including Heather and Katie, about what books they had read with their students, and I listened to the students as they drove the discussions all year.

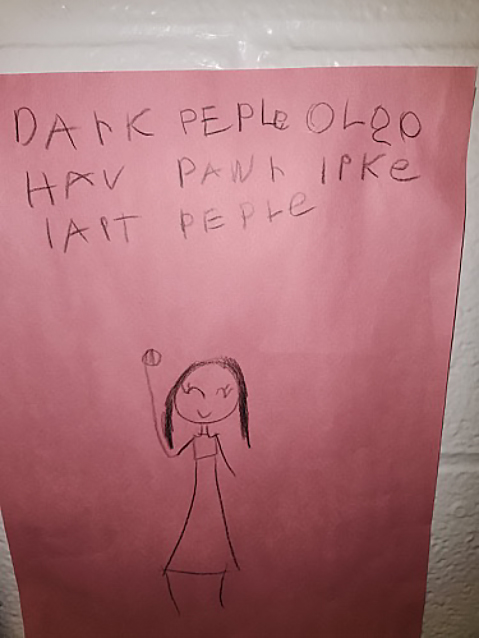

In May, near the end of the school year, the students showed in their communication what had come of our discussions. We had a new student just arrive in our classroom from another school. He had told a dark-skinned student, “I don’t play with dark kids!” Bisrat was nearby and overheard this comment. She stated, “The skin you have is the best colour for you! All colours are beautiful.” Another student, the following week, spent a large part of the morning drawing and writing at the Art Studio and came to me and said, “I made a poster. I want to put it up in the hallway in the school.” I asked her to show me the poster. It was a picture of herself. Amina was one of the students who had agreed with the comment earlier in the year that light skin was more beautiful than dark skin. She had dark brown skin. Amina had drawn herself and written the words “Dark people olso hav pawr lik lait peple” (Dark people also have power like light people). She said, I want to put it up where everyone in the school can see it. I asked why, and her response was, “Everyone should be talking about the stuff we talk about.”

Beloved community is formed not by the eradication of difference but by its affirmation, by each of us claiming the identities and cultural legacies that shape who we are and how we live in the world.

—bell hooks, Killing Rage: Ending Racism

Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop (1990), speaks of books being windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. The books we read and reread and the conversations we have surrounding texts that allow children to see themselves, see others, and enter into worlds and conversations that may be familiar or unfamiliar to them provide the foundation for our year of learning together. They allow us to question rules, assumptions, and ways of being in the world that may be new or familiar to us. They create opportunities for children to share their stories and for the community to honor those stories. Starting with powerful read-aloud opportunities provides spaces for children to tell their stories. It is up to us as educators to dream boldly and provide the safe space for children to tell these stories, for the community to listen to these stories, and for dialogue to occur to support children in questioning, wondering, and making sense of the world we live in. It is not easy, but our children deserve this.

If you are looking for professional resources and children’s books that can support this work, click here for a few examples of texts we have used.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: A Review Journal of the Cooperative Services for Children’s Literature, 6(3), ix-xi.

hooks, b. (1995). Killing rage: Ending racism. Henry Holt and Company.

Biographies

Katie Keier has been a classroom teacher, school librarian and literacy specialist in grades preK–8 for 34 years. She is currently a kindergarten teacher in a Title I school near Washington, DC. Katie is passionate about play, literacy learning, agency and access for all learners, arts integration, and Reggio Emilia-inspired pedagogy. She is the coauthor of Catching Readers Before They Fall and writes on the www.catchingreaders.com blog. When she is not learning and playing with young children, she can be found running and playing on the trails in the mountains of Virginia.

Heather Olah is an elementary vice principal in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Prior to becoming a vice principal, she was a classroom teacher with a passion for kindergarten and literacy. She also supported and mentored other teachers as an early reading coach and school improvement process coach.

Nick Radia is currently a kindergarten teacher with the Toronto District School Board. He has over 25 years of experience teaching or coaching early years classrooms. He has helped transform the equity and pedagogical practices of multiple schools and educators in formal and informal roles as a central coach, mentor, and Position of Responsibility (POR). He has consulted for system officers, centrally assigned principals, and school-based principals and teachers who have sought his expertise in transforming their approach to equity and pedagogy within their classroom or staff. Using intentionally chosen read-alouds as provocations for big discussions and questions to explore critical consciousness is a crucial part of his anti-oppression and inquiry-based pedagogy.